Another week — say it with me now — another game against a teenager. And a teenager I’d played against before, at that.

Last Monday saw a rematch between me and my opponent of July 2, 2024, which I wrote about in my post “When Should You Take a Risk?” Unfortunately for me, in the eight months since that game — a game I should have won, then should have lost, then drew — said teen gained 250 rating points. Kids!

What’s unfortunate isn’t that this happened: what’s unfortunate is that I knew this had happened, and I could go on the USCF website and look at the recent tournament in which he beat one player who was rated 2000, drew another player who was rated 2000, and then drew a guy rated 2132.

This knowledge put me at a disadvantage right off the bat. It made me believe, first of all, that this guy is really good, and second, that he’s on a hot streak. Sure, I told myself in the car on the drive over that I had almost beaten him just a few months earlier, and I could certainly beat him now, but based on how the game ultimately played out, it’s clear that my preconceptions outweighed my positive self-talk — because I played like I was already losing before the game even began.

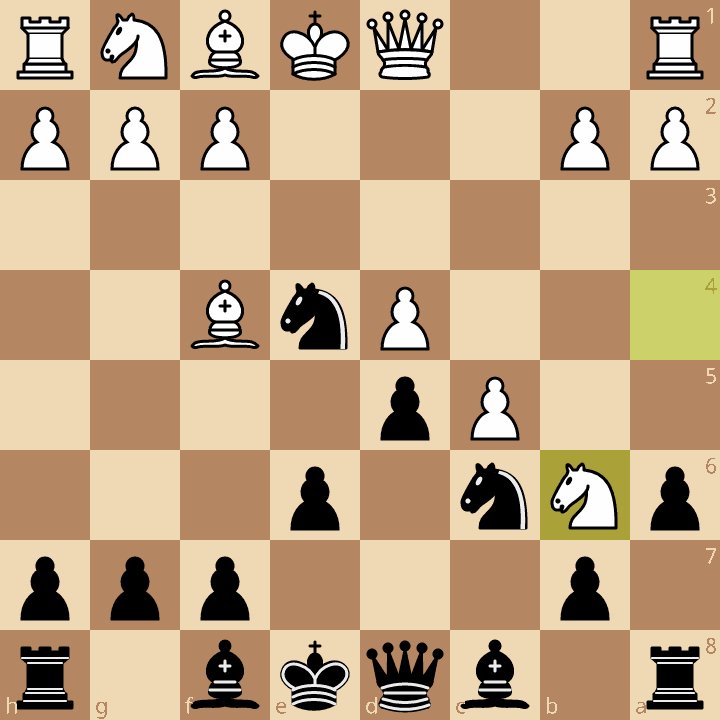

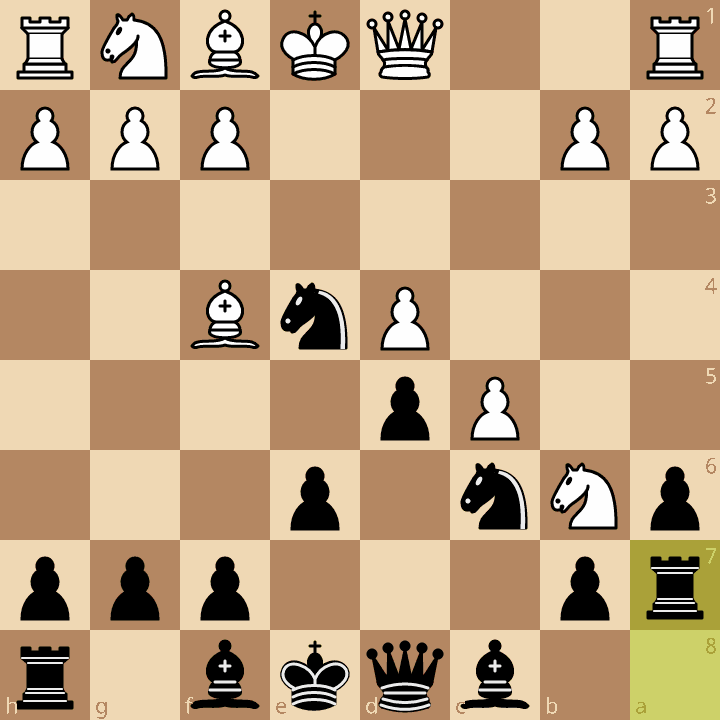

So what happened? Let’s take a look at this position, reached on move 9:

I’ve decided to try again to do the deeper chess analysis in a video so that the post doesn’t get too bogged down with lines and variations. If you’re interested in that, watch below. If not, skip it.

Okay — so, broad strokes, what’s going on here?

White is attacking quite aggressively. He’s moved his knight three times in the first nine moves. You’re generally not supposed to do that. Staring at the board, I knew, very well, that you’re not supposed to do that. And while the result is that he’s plugged said knight into a beautiful outpost square deep in my position, where it’ll be hard to dislodge and is attacking my rook to boot, I still had the nagging sense that White’s position had weaknesses I could exploit because of this inveterate knight-moving.

The problem? I couldn’t find these weaknesses. There’s no obvious attack. My bishops are horribly confined. My rook is hanging. And to make matters worse, this is a position well outside of my prep — I don’t have any familiarity with this type of structure.

One move did cross my mind: the e5 pawn-break. When your position is cramped, the typical strategy is to open it up, which e5 would do. But I took one look at that move and saw that White had e5 sufficiently defended. And what about my rook??? Am I just gonna let him take it? Even if that would mean his knight moving a FOURTH time in the first ten moves?

No way, buddy. Not today. Instead, I pushed my rook to a7, even though this is horribly depressing. It’s such an ugly move. It makes me sad just thinking about it.

To make a long story short, the game went downhill from there. I played defensively, I never managed to get any space, and eventually I got mated after a nice, Greek Gift-esque tactic.

It was a badly played game, and on top of that, it wasn’t very fun. I spent the whole time following my opponent’s lead, trying to wriggle out of the squeeze he’d put me in. It reminded me of the times when, while training Brazilian jiu-jitsu, I’d get caught in a choke and slowly realize there was no escape. In such situations, you have two options: tap or pass out.

Of course, there is always a third choice: fight back. Go on the attack. Take control.

The problem is that such a reversal is easier said than done. It isn’t as if, during the game, I thought to myself, “Oh, jeez, I guess I should just let this kid destroy me.” I knew I needed to strike back. But such knowledge, coupled with an uncertainty as to how to actually do so, ultimately just makes you more anxious. Wiping the pieces off the board with my arm and storming out of the San Marino Masonic Lodge would’ve been one way to strike back, but it wouldn’t have helped me win the game (or get invited back to the next tournament).

While there’s plenty of research about the value of a sense of control in a person’s life, there’s also compelling evidence that the removal of control can be extremely disturbing. That means, when you’re playing a chess game, or engaging in any other kind of competitive situation, and you experience that feeling of the loss of control that happens so often, you not only need to be able to regain control somehow — you need to endure the experience of losing it.

Now, this is a serious problem for all human beings: responding to it is one of the central priorities of entire systems of philosophy and belief. (Buddhism being the most obvious example). These traditions tend to understand that the urge to take control back, to respond with aggression and assertiveness, can merely serve to compound your anxiety. Clinging, etc.

So what do you do, if not scramble to retake control? Let’s think about the problem from a different angle, one that shifts the emphasis from a need for control to a different focal point: the opportunities, rather than the costs, of being reactive.

Most people have probably heard of the “first-mover advantage,” which states that the first company to go to market in a particular area has an inherent edge. Ironically, when you Google it, you discover that one of the most common illustrations used in articles about the concept is a chess player making the first move with the White pieces. But anyone who knows anything about chess understands that the first-mover advantage has little to do with playing as White1 — it has to do with who initially gives the game its unique character, its feel and tone and narrative. White can do this, but so can Black — here’s a good example from one of my OTB games, where Black went on the attack before White did.

Another general example is 1… c5. Sure, White moved first, but it’s Black who says, we’re playing a Sicilian, and there’s nothing you can do about it. I don’t care how much Ruy Lopez prep you did.

In the game I’ve been discussing, White took the first-mover advantage not by playing the first move, but by closing the position with c5 on move 6, determining what kind of game we would be playing, at least to start. It would be a strategic, positional one, and the decisive factor in the opening would be who could make their pieces more active.

First-mover advantage is a well-known phenomenon — but there’s also such a thing as second-mover advantage. The general gist is that, by moving second, you not only have more information than the person or business who goes first; you also have less of a sunk cost, meaning that you can shift and adjust more easily.

There are plenty of examples of this in the business world, with Amazon being the most notable. (Do you remember “Book Stacks Unlimited”? Neither do I!) But I think it has relevance to any competitive situation, the idea being: rather than obsessing over control and initiative, focus on being responsive instead. Not passive or reactive: responsive, meaning that you take the information that you’re offered and use it to your advantage.

BJJ is all about this kind of behavior. One of the most surefire ways to submit your opponent is to get them to overcommit, whether in terms of weight or space. If they put their hands too far into your area of control, then you might have the chance for an arm bar. If they’re leaning their weight too far forward, you might be able to catch them in a triangle choke. If they’re too aggressive, you might use their momentum to flip them.

This is the second-mover advantage in action: you have something to work with. Of course, if you don’t respond intelligently to these attacks — if you merely try to turtle up and defend yourself — you’ll be the one who gets submitted. So it’s essential that, whenever you’re in the position of moving second, you’re always looking for the opportunity to use that information you’ve been given to your advantage.

Cornerbacks in football are also specialists in the second-mover advantage. The counterattack in soccer is another instance, as is the fast break in basketball. It’s everywhere in sports, and often, it characterizes the truly sophisticated, dangerous teams and players in comparison to the ones who just try to force their will regardless of the circumstances.

Let’s go back to my game. As I pointed out, I knew that White had been overly aggressive, and had been playing in an unprincipled manner. And I knew that the way to respond to such play was to open the position, using his aggressiveness against him. I even saw the way to do this: e5, which I had actually noticed and considered on the previous move, when White’s knight was still on a4.

But I didn’t look at e5 through this lens: I looked at it purely as a chance to exchange material, and after my quick analysis revealed that White had it covered, I abandoned the idea.

There’s a concept that’s become popular in chess called the Sam Shankland Rule, named after the American GM who coined it. It says that, when you see a move you’d like to play, and that idea doesn’t seem to work, you should ask, “What if I play it anyway?” The top trainer GM Jacob Aagard expands it a bit to essentially suggest that, if a move looks good to you instinctively, you should try harder to make it work before you abandon it.

If I had kept the Sam Shankland Rule in mind, then I would’ve seen that, even with White attacking my rook, e5 still works. The idea is that, if White grabs the rook, then I can take the bishop. White has to spend a tempo getting his knight out of the corner, and that allows me to move my queen to h4 — threatening mate in one. All of a sudden, Black is better. And if White doesn’t grab the rook — if he stops to exchange on e5 — it’s even worse: Bxc5 is devastating.

I had a definite second-mover advantage in this position — the chance to use White’s momentum against him. To prove that Instead, I let him dictate the position, and I tried to play his game. Because of that, I lost.

You’ve probably heard the quote, usually misattributed to Victor Frankl, “Between stimulus and response there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom.”2 This is, essentially, the second-mover advantage. Choose your response! Embrace growth and freedom! Don’t make the sad rook move!

There is a long and complex debate about how valuable it is to have the White pieces, but let’s just say that at my level, it doesn’t really matter: either side is just as capable of making a dumb move.

Turns out, Stephen Covey just found it in a random library book and was like, “This sounds a lot like Frankl!”

Nice post Kevin, e5 is not easy to see! (or more precisely to not dismiss instantly)