Good Moves: a newsletter

Introducing Good Moves, a newsletter about chess and what it can teach us about performance in all parts of life.

An introduction to this newsletter.

On Tuesday evening, I left my wife and four-month-old baby at home and drove half an hour to a church in Altadena, where I spent the next two-and-a-half hours sitting in silence across a folding table from a 12-year-old.

Is this a normal thing to do? No! But did I have a good reason for doing it?

I… think so?

I was playing chess.

“Chess?” you might say, head tilted in recognition. “Don’t people just do that on their phones?” Yes, they do. There has been much made of the chess boom since the pandemic, with untold billions of bored teenagers from former Eastern Bloc countries playing one-minute bullet online and then chatting “lol u suk 😂😂😂” when you inevitably lose to them.

But people also play chess in person — and this is the kind of chess I’m really interested in. Referred to as “over the board,” or OTB, and regulated by the United States Chess Federation, or USCF, rated in-person chess is usually played in the form of either weekend tournaments or local clubs.

I happen to play at the San Gabriel Valley Chess Club, which meets at said church in Altadena every Tuesday night. There are usually anywhere from 40 to 60 people there, ranging in age from literally six-year-olds all the way up to, like, the oldest guys you can imagine. (Seriously, try and imagine. No, older. Older.)

“Ah, chess clubs,” you respond, nodding with further recognition, nodding vigorously. “I’ve heard of that.”

NO, NOT THAT.

I mean, that’s fine. I’m all for brands doing chess. The more, the merrier. If you are a brand and you want me to do chess for you, please reach out.

There are also casual, non-branded chess clubs, where people meet in bars or parks and play blitz (five-ish minutes a side) or bullet (two or one minutes a side). I’ve gone to those, too — shout out to the Los Feliz Chess Club, which meets in Griffith Park every Sunday.

But the key difference here is that the rated games I play at SGVCC are 90 minutes per side. That means each person has 90 minutes to make all their moves. That means the games can last as long as — well, you can probably do the math, but the answer is three hours.

This is the chess that I like. This is a different kind of chess. But this is also a kind of chess that is very time-consuming, very demanding to do well, and very… intense.

Even before my son was born, I would come home from these games and be wired, sleeping poorly, waking up the next day in a state of mild delirium. At one point, justifiably bewildered by this, my wife, Alina, asked me why I liked playing chess so much. “When you lose, you’re upset,” she said. “And when you win, you seem even crazier.”

It was a very good question. I had an easy answer for why I like playing OTB: it’s a flow state. When I’m playing, I can think about one thing, and one thing only, for two, two and a half, even three hours. How many things in your life can you say that about?

But this question has larger implications: why do I feel compelled to spend so much time improving? Why do I care about my rating? What is the point? Is it merely to escape into another world for two to three hours a week? Or is there something deeper and more significant going on here? The truth is that I spend way more time than just those two to three hours on chess, and some of it is monotonous, difficult, and kind of annoying: drilling tactics, memorizing openings, and so on.

One of the effects of having a child is that it quickly clarifies what is important to you. Spurred on by a big crunch in your amount of available free time and the sudden, startling appearance of a little creature who instantly becomes the most meaningful thing in the world, you have to make some stark decisions about what you want to actually focus on when you do have those half-hours to yourself. You just can’t possibly do all the things you used to do. If you want to do anything that isn’t scrolling on your phone, you need to be deliberate about it.

What I rapidly realized, within days of my son’s birth, was that I wanted to keep playing chess — but not just playing it. Studying it, understanding it, and competing in person. Before he was born, I knew that I loved chess. But after, I understood that something about chess was essential to the way I’m trying to live.

This newsletter is, first and foremost, an attempt to answer my wife’s question. Following from that, it’s a project to make the most of the time I’m spending on this thing that has possessed me so strongly, and to concretize and absorb the lessons that I might otherwise overlook… which should hopefully make me better.

By extension, I want it to serve that purpose for you, the reader, as well: to illuminate the lessons that can be learned from this pursuit. To treat it as a microcosm of life, with takeaways that can then be applied to the macrocosm. The idea is that you could basically substitute any pursuit, from hobbies to work to sports, that you spend meaningful time on and still understand what I’m getting at, and use what I’m learning about my own play to improve your own moves in whatever field it is that you’re making them. The key is that you spend “meaningful” time on it: you study it, you try to get better at it, and you perform it at a high level, with some degree of stakes.

Part of my argument is that said pursuits are, if not essential to living a good life, then very helpful for doing so. But we’ll get more into that as we go.

Here’s the format. Each week I’ll share a position from my OTB game. If I didn’t play an OTB game, then I’ll try to use an online game, or some other chess-related activity. And after explaining the position, I’ll share my thinking about it and how that helped me realize some larger takeaway about my psychology both in and outside of chess — an idea that, hopefully, could be applicable to something in your life, to whatever your chess is.

(And if you don’t have a chess of your own? Consider trying one out! I am more than happy to offer my thoughts on how to get into a hobby if that proves appealing.)

There are many chess-improvement newsletters, and there are many performance-improvement newsletters. I’m hoping this one can carve out a space in between, where it appeals to chess players as well as people who don’t know how a knight moves. Because a lot of chess writing ends up acting like chess is just a game.

What this newsletter presupposes is… maybe it’s not.

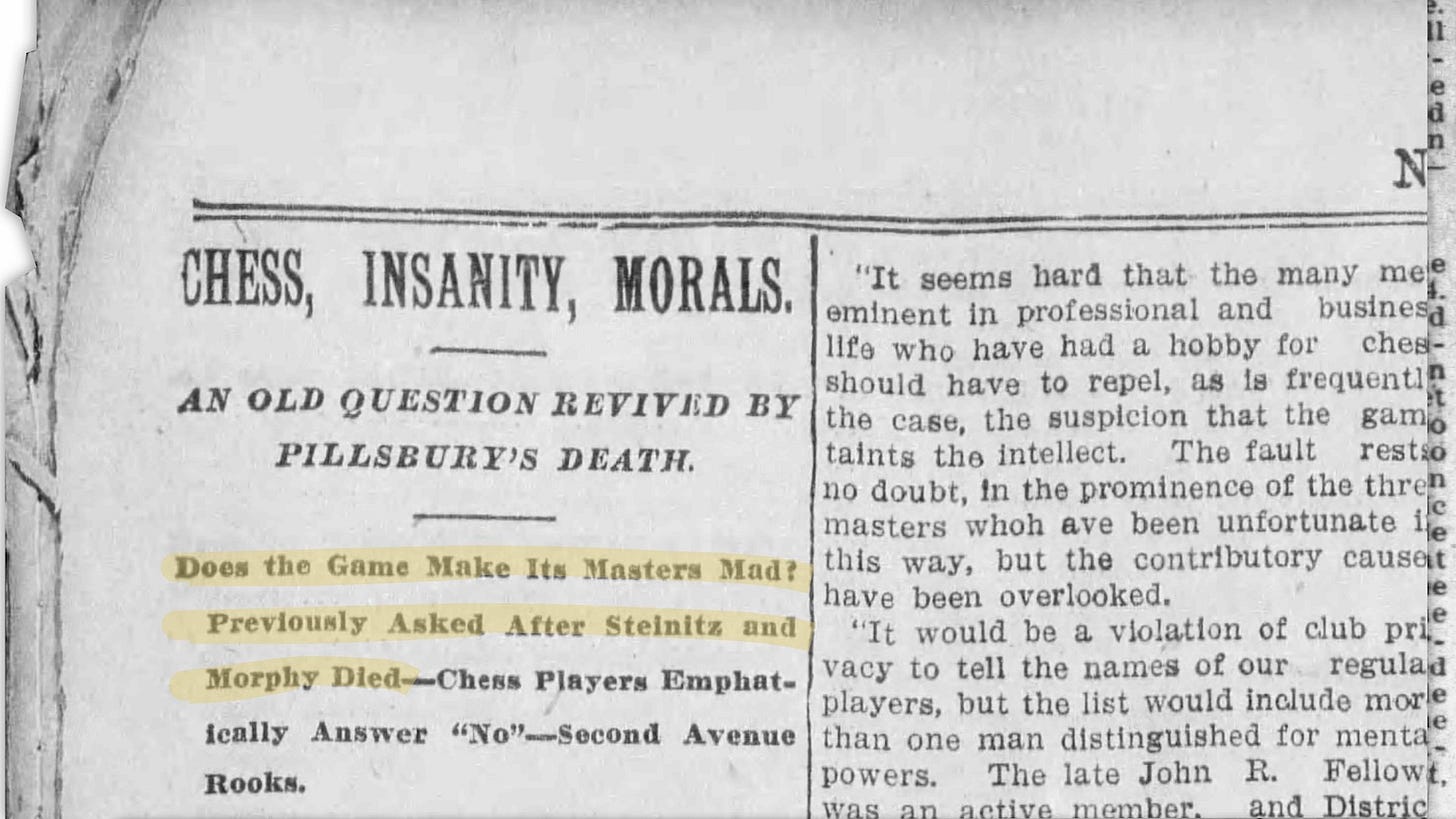

There’s this stereotype that chess drives people insane. There is some truth to that. That’s why it’s worth doing, just like rock climbing or Brazilian jiu jitsu or ultramarathons (or, for that matter, studying quantum mechanics or being a parent or writing a novel) are worth doing. They push you. They force you to improve. They’re hard, and they have risks.

And chess in particular is endlessly rich in this respect because it’s a perfectly closed system. There are no variables, no day-to-day fluctuations. It’s the same board and same pieces every time. (This, not coincidentally, is also why it has the power to drive people insane: it is a world so rich and complete that it can start to replace the real one.) This is why it’s such a valuable and fascinating psychological endeavor. Every time you play a game, it’s an experiment that you’re running on your own mind.

If this newsletter has any point, then, it’s this: the stuff that’s worth doing is hard. But to be worthwhile, we need to do it consciously, mindfully: we need to try to understand what it is we’re doing, why, and how we can get better, not just at it, but at everything.

I hope, soon, to expand the format: interviews, additional chess analysis and lessons, videos, etc. Ideally, we can build a community here. But let’s start simple.

My credentials.

So why should you listen to me about any of this? Great question!

As far as chess goes, I’m pretty good, but not great. My USCF rating is a provisional 1652, which means I still need to play a few more games before it becomes official. That puts me right around the top 10% of players — but that’s obviously a self-selecting group, the people are serious enough to pay money for a USCF rating and play OTB.

My chess.com rapid rating ranges between 1500 and 1700. That puts me in the top ~2-3 percent of players on chess.com, which is a highly not self-selecting group, since it takes all of about 20 seconds to make an account there.

One thing that’s also worth mentioning, though, is that I learned how to play as a kid, but I only learned how to play well as an adult — meaning that I’m highly conscious of my journey as a chess player, and of what it has taken to get to this level in a pursuit I committed to around 30 years old.

As a writer, I worked at New York magazine, and I’ve been published in the New York Times Magazine, GQ, The Wall Street Journal, and many other fine publications. I now work as a documentary filmmaker and book collaborator, which essentially means that I help people write books.

Altogether, the bet I’m making here is that I’m a decent-enough chess player to have meaningful insights, and that I’m a good-enough writer and communicator to be able to articulate them in a way that will be both enjoyable to read and might actually help you learn something.

Okay. Enough preamble. Let’s look at some chess.

A Position.

One of the qualities that I love about chess is that it is, more or less, an ideographic language. Any position from any game contains an immense amount of meaning, and how good you are at chess exists in direct proportion to how well you can read the meaning in that position. It doesn’t matter how we got here; any player can pick up a game at any point and come up with a plan for what to do next. This is one of the qualities that makes chess so deep and artistic, and why it appeals to a person like me, who makes his living by crafting stories.

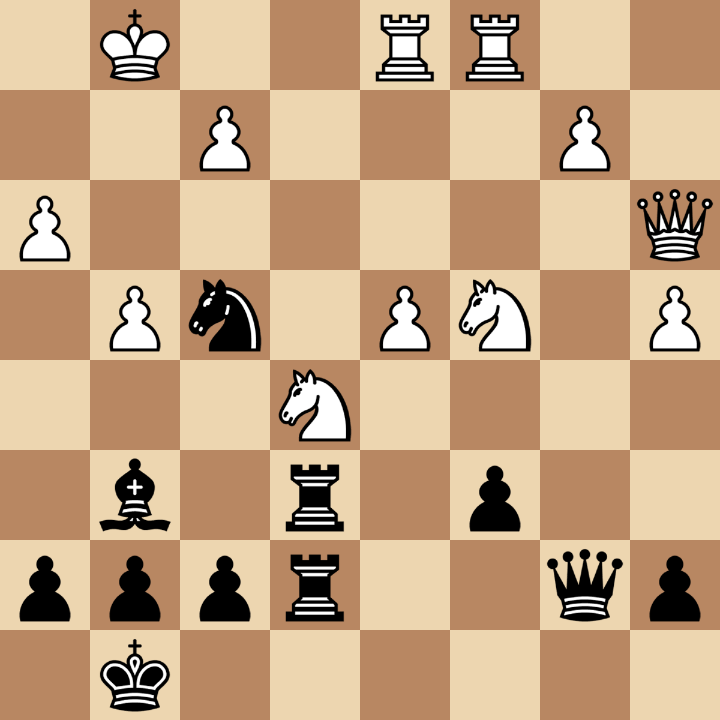

This is from my game on Tuesday. I’m playing with the Black pieces. My opponent was rated 1922. That’s pretty good. 2000 means you’re an Expert, according to the USCF; 2200 gets you the title of National Master. Even if I maxed out the time I could spend dedicating to chess for the rest of my life, it’s likelier than not that I would never reach 2000. Seriously. It’s really, really hard to get there as an adult. My pipe-dream goal is 2000, but 1800 is my more realistic target. (There have been very heated debates about this in the chess world: here are two sides of said debate, arguing about whether an adult chess-improver named Neal Bruce can make Master.)

And it just so happens that my opponent is 12 years old, meaning that he’s still got a lot of improving to do. I believe he either was or still is ranked in the top 100 nationally at his age.1

But I was happy to be in this situation: I vastly prefer to play against opponents who are rated higher than me. There are a few reasons for this, and I think they offer a pretty apt glimpse of where I’m psychologically at at this point in my life. You can divide them into Good and Not-So-Good Qualities:

Good Qualities: I want to be challenged. I want to improve and don’t mind losing in order to do so. I thrive as an underdog, and I can play up to my opponent.

Not-So-Good Qualities: I am more focused on my rating (read: how other people see me) than I should be, and I don’t want to lose the rating points that come from a defeat at the hands of some underrated kid who’s at 1300 now but will be 1700 a year from now. I get anxious when I’m the favorite. I fear that I’m worse than my rating says I am, and that I will be exposed if I play lower-rated players. Paradoxically, this manifests as cockiness — I don’t take threats seriously when a lower-rated player is posing them, and this has cost me games before.

We reached this position on move 27. I can’t remember exactly how much time had passed, but it was at least 90 minutes total. Once we got here, I knew that we were at a crucial juncture in the game, and I suspected that we were just about even — an evaluation that the engine later confirmed for me.2 That’s pretty good, considering how much higher-rated my opponent was. I knew I had a chance to either draw or win, though it would be an uphill battle still.

It’s at this point that I notice something. If I can land my knight on f4 and clear the c6 pawn out of the path of my queen, then I’d have checkmate on g2.

Checkmate. The one factor that makes all others irrelevant. That’s the funny thing about chess: you could be down two pieces and a queen, with one second left on your clock, and still win if you can find checkmate.

I can either chase this checkmate, or I can play a smaller, more subtle move that strengthens my position. The problem with the former plan, though, is that I’m sort of counting on my opponent not noticing what I’ve just noticed: there are ways to stop this from happening.

Now, in more detail, here’s what’s going on in this position.

***NOTE: YOU CAN SKIP AHEAD TO THE NEXT BOLDED ASTERISKS IF YOU’RE NOT A CHESS PLAYER, SINCE I’M ABOUT TO GET DEEP INTO CHESS STUFF***

White’s kingside pawns are weakened, but he has great piece activity, especially with his knights, which are protecting each other right in the center of the board. They’re monsters; they’re basically the Two Horsemen of the Apocalypse. He’s up a pawn, so if we go into an endgame he’ll have an advantage — meaning that I want to keep pieces, and therefore checkmating chances, on the board. I don’t just want to trade everything. His d-pawn is isolated and therefore weak. But he also owns the d6 square, and if he puts his knight there, he’ll land it with a tempo on my queen, which would be… uncomfortable.

Meanwhile, my knight is on a solid outpost, meaning that it’s protected by a pawn and it can’t be dislodged by a pawn. That’s good. I have a bishop, which is generally considered a small advantage, but my bishop isn’t really doing anything — it’s been sitting on that square all game, and at any point, White could trade his knight for it. I’d actually been hoping he would do that so I could open the f-file and point my rook at his kingside, but he understood that that would be a mistake and has held off from exchanging his strong knight for my weak bishop. This would’ve also solved another problem, which is that my king is trapped on the back rank. It has no escape route, meaning that I’m vulnerable to shenanigans that would allow White to plant one of his rooks or queen back there and checkmate me. That’s bad.

One commonly accepted idea about chess is that you’re essentially playing for two resources: time and space. When you have time, it means that your moves are driving the action, and your opponent has to react to them rather than the other way around. When you have space, it means that you control more of the board, and you’re both more able to attack and less vulnerable to attack. You’re often trading one for the other.

At this point, I have a decision to make. White has just played Rac1. For the first time in a while, I don’t have to react immediately to his move. I have some degree of initiative. I can either: a) try to solve my space problem by moving one of the pawns around my king, thereby eliminating the back-rank dangers; or b) I can attack, trying to win a tempo and take the initiative as far as time goes.

It’s at this point that I notice something. I’d been eyeing the f4 square for my knight for a while now, but I had been prevented from putting it there by a combination of White’s dark-squared bishop and his queen. However, White recently traded off his dark-squared bishop for mine, and he moved his queen to the other side of the board. That means that, now, the f4 square is free for my knight, and if it lands there, it will have a double attack, threatening both h3 and e2 with check and a fork against the rook.

And then, of course, there are the checkmate chances on g2. Checkmate is always the best move.

So I arrive at two possible candidate moves, i.e. choices for how I can proceed.

I can play something like h5, eliminating back-rank mate possibilities and further undermining White’s kingside pawn structure. Unfortunately, I don’t quite see the follow-up: it isn’t fast-enough of an attack to maintain the initiative. Or:

I can play either Nf4 or c5, both of which would pave the way for checkmate on g2. c5 is a little stealthier, but it also doesn’t attack anything, meaning that it gives White the opportunity to interrupt my plans. I’m not totally sure how he’ll do it, but I came conscious of the essential importance of speed here, of maintaining the initiative, and c5 just feels a bit too slow, even though it's more subtle.

I play Nf4. Seize the day!

A Lesson.

***IF YOU SKIPPED THE CHESS STUFF, YOU CAN START READING AGAIN***

Everyone knows the saying, “It’s better to be lucky than good.” And, often, it is! Luck is a factor in every single competitive endeavor. At a fundamental level, you just don’t have full control over the outcome: your opponent could be sick, or you could meet an agent at a party who wants to publish your book, or whatever.

But I’d like to propose a corollary to this: “It’s better to not have to get lucky.” When we start out doing something, we often rely on a certain level of luck to get wins, because we just don’t have the core competency to be able to guarantee victory. I remember this from my days doing Brazilian jiu-jitsu: I would constantly launch ill-advised triangle chokes against my sparring partners, relying on the element of surprise to get my legs around their necks before they could react. The low skill-level of your competition means that they just don’t have enough ability to always exploit your mistakes.

In such circumstances, activity becomes the most important aspect of winning: creating more chances for yourself than your opponent does for them. So if you’re a beginner, you’re probably right to focus on just doing stuff, generating tons of mistakes that you can learn from, and not being afraid to fail. You miss every shot you don’t take, etc.

The better you get at whatever you’re doing, though, the better your opponents get. This is as true in a zero-sum sport like chess or BJJ as it is in, say, television writing, where, if you want to get your show made or get in a writer’s room, you need to be at least as good as all of the other professionals trying to do the same thing. It isn’t enough to hope you’ll be discovered. There are too many bars to clear: too many points at which you might not get lucky anymore. Everyone you meet is looking for a reason to say no to you: you have to not give them that reason. (Again, there are plenty of other elements that might give them this reason — budgets, their bosses, their own fear of failure! But it shouldn’t be you.)

Therefore: the higher you rise in a field, the less you can rely on luck. Your competition is just too good. It’s still great to get lucky, and luck will remain a part of your success, but luck can no longer be something you plan on.

By playing Nf4 and launching this premature, refutable checkmating attack, I’m indulging in what the late, great IM Jeremy Silman calls idiot chess3: a plan based on the other person making a mistake. I’m hoping my opponent will miss the danger of g2. But he’s too good for that. If I saw it, and I’m nearly 300 points lower-rated than he is, why wouldn’t he?

I’ve reached a level where, if I want to continue getting better, and I want to beat players that are higher-rated than me, then I need to pretty much assume that, if I see something, they’ll see it, too. Rather than hoping that they miss what’s happening on the board, I need to engineer situations, through good strategic play, in which, by the time the tactic appears, it’s too late to do anything about it.

Here’s how Bobby Fischer put it: “Tactics flow from a superior position.” He said that of an absolutely beautiful game against James Sherwin in 1957, which he writes about in My 60 Memorable Games. If you want to see what really great chess looks like, watch this.

Let’s say I was playing with this idea in my head: that it’s better to not have to get lucky. What would I have done then? I would’ve seen that h5 didn’t really lead anywhere, and I would’ve seen that Nf5 was too easily refuted. Then I would have had to ask, what can I do to undeniably improve my position?

Thinking this way, the answer becomes simple. I need to think about what advantages my opponent has — and the best thing he has going for him right now is the move Nd6, hitting the queen. If I can take that away, then we’re back to being just about equal. The best way to do that is by moving my queen to a square that can’t be attacked by the knight. Ideally one that has some influence over the board. Like a6.

If I had played Qa6 there, we would’ve had a sharp, volatile position that still could’ve gone either way. But I would have had real drawing chances, and a draw against a player that much better than me is a huge win. Unfortunately, I got distracted by the shiny object, and I tried to play for the cheap attack, and I ended up getting punished for it — I resigned within 10 moves.

So yeah: this is a nice lesson for the first issue of Good Moves. Next time, make the move that you know is good, and don’t count on getting lucky. Let your opponent be the one to make the mistake. In every position, there’s always a best move; and if you can see the flaws in your approach, that means someone else can, too.

What I’m watching, reading, and listening to.

In the future, I want to make more recommendations here, but because this is the first newsletter, I’m going to focus chess. Right now, the World Championship is taking place between reigning champ Ding Liren and 18-year-old challenger Gukesh D. It’s very interesting, for a lot of reasons, and despite some expectations, it has, so far, been a close match: they’re each tied at 3 points after six games.

The game is happening in Singapore, so most likely you won’t watch live. My preferred way to follow is through the many video recaps that are posted on YouTube. If you’re relatively new to chess, I’d suggest GothamChess or ChessBrah; if you’re more experienced, I’d point you to Hikaru Nakamura or the Take Take Take recaps with Magnus Carlsen, the greatest chess player in the world.

For those reading this who don’t regularly play OTB chess: one of the most fascinating aspects of it as a Thing You Do With Your Life is that you’re constantly playing against kids. Kids are not like adults, in case you haven’t noticed, and in chess, that tends to manifest in a few different ways. They’re usually getting better rather than worse. They’re usually sharper than an adult at their same rating level, meaning that they can spot tactics and patterns an adult might not, but they tend to have less knowledge, so sometimes they’re strategically a bit behind. A lot of times they play really fast, but that’s not always true. Also, the games go past their bedtimes.

A note about chess engines: they are a very useful tool for helping you improve, if you use them right. In this sense, they’re like any technology. You can either outsource to them the judgements and skills that you would otherwise be using yourself, or you can use them to help you develop these judgements and skills by comparing yours against theirs to make sure that you’re right. I try to use the engine after I’ve already evaluated my own game.

I actually can’t remember exactly what Silman calls this, but it’s something along these lines. “Idiot tactics,” an “idiot plan,” etc. The point is that Silman first alerted me to the idea, and that it involves idiocy founded on being lucky rather than being better.

Replace Nf5 by Nf4 and d3 by d6.