Good Preparation Is Great — But Bad Prep Can Be Worse Than None at All

How the Einstellung Effect explains bad opening play... and the world.

The opening dilemma

How much should you study openings?

This is one of the most hotly debated questions in the so-called “adult improver” chess community. For those of you not neck-deep in this world like I am, the gist of the argument centers around the fact that “opening theory” in modern chess — i.e. the optimal way to play the beginning of the game — can often reach 30 or more moves per line (including White’s moves and Black’s responses), with hundreds of possible lines branching out from any given first move.

That’s a lot of memorization… and instead of memorizing these moves, you could just follow the fundamental opening principles: develop your pieces, occupy the center, castle early. That requires no memorization, and it generally works pretty well below master level. Or so the story goes.

There are extreme examples in either direction. If you spend enough time in the chess community, you’ll no doubt encounter players rated below 800 who are working through some 1,000-plus line Nimzo-Indian Lifetime Repertoire, and master-level players who say they’ve barely studied openings at all. I don’t think either approach is advisable. So what’s the healthy medium?

I can only speak from my own experience, but it suggests that having some opening knowledge is advisable if you’re a serious club player who’s trying to improve. At the same time, you should know the plans within the opening, not just memorizing a bunch of lines; again, this is generally held to be the best way to study openings. I’m not saying anything controversial here. And I’ve found that my opening study has been a good way to better understand strategy in the middlegame as well — which, after all, has to arise from the opening.

What I do think might be a more unique take is the one that I developed after my club game last week: opening study is great, as long as you know when to forget it.

Caro-Kann or Caro-Kann’t

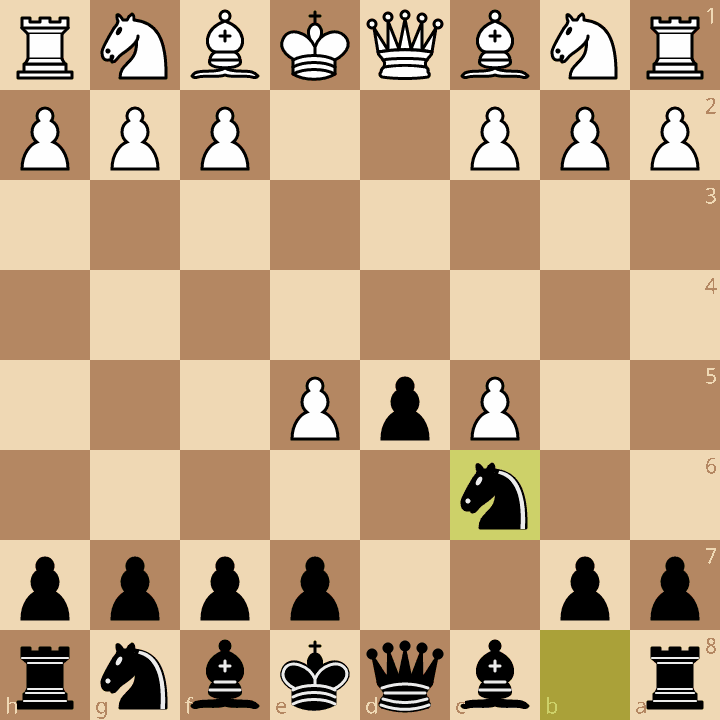

Here’s my position after Black’s fourth move. I’m playing against a strong teenager with a rating in the mid-1800s. Any chess player with opening knowledge will recognize this as a Caro-Kann Advance in which White played the optimal response, 4.dxc4. The more popular response, 4.c3, isn’t as good, meaning that, as soon as White played 4.dxc4, I knew he had some knowledge of how to handle the position.

I was not, however, ready for the next move.

f4 always strikes fear into my heart. It can be a risky move to play, weakening the kingside, but that means that, when you see it on the board, it’s often coming from someone who knows what they’re doing.1

Worse than that, though, is the fact that I had never seen this move before. White’s more typical response in this position is to play Nf3, in which case I would have responded Bg4, pinning the knight and getting my bishop clear of the pawn chain. This is what I usually see when I get this position online, and it’s what I’ve studied so far in the Caro-Kann opening course I’m working through.

But here’s the interesting part: although 5.Nf3 is the most common continuation, it still only happens 41 percent of the time, according to the Lichess database. That means I was more likely than not to get a line I hadn’t prepped for once we reached this position. And that was only after four moves!

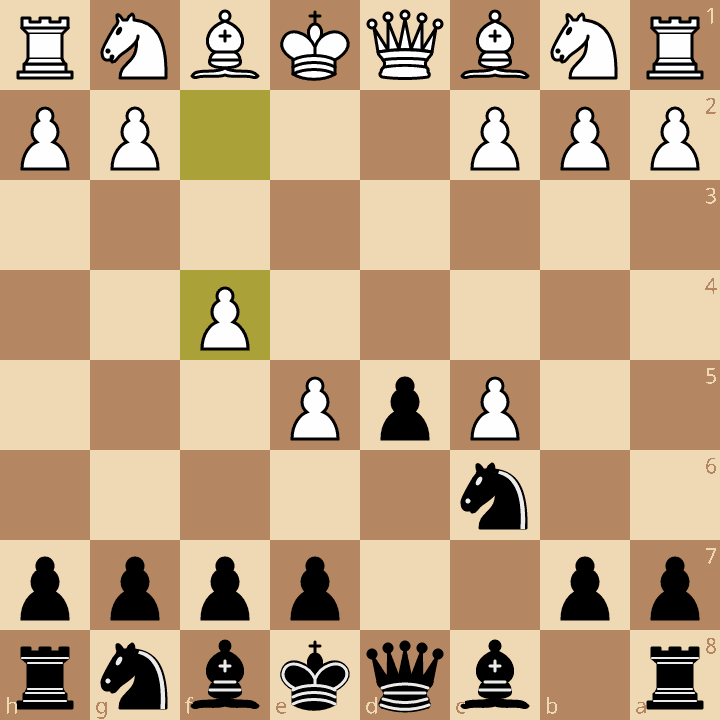

When White played 5.f4, I was out of book, as they call it when you no longer have opening lines to fall back on. So what did I do? I looked at the position, and I remembered another line where White plays f4:

This is the position that arises when White plays the more popular, but less good, 4.c3 move instead of 4.dxc4. I knew that, in this position, Black should play 4.cxd4 and then develop the c8 bishop to f5.

Looks pretty similar to the one I’d found myself in, right? How different could it be! My opening prep had served me well after all.

I played 5.Bf5… getting myself into a world of hurt.

Strong but wrong

Last week, we discussed anchoring bias — the idea that prior information can influence your present decisions, even when it isn’t good or relevant data. But this is a pretty broad category, encompassing many different types of so-called “anchors.” The anchor could be a once-useful but no longer relevant data point, or it could be something that didn’t even make sense.

For example, as I mentioned in that piece, if you tell someone that Gandhi died at nine years old, they’re more likely to underestimate the age at which he died when they are asked to guess, even though they know that he couldn’t have possibly died at nine. If you suggest that he died at 140 years old, they’re more likely to overestimate the age at which he died, even though… you get it.

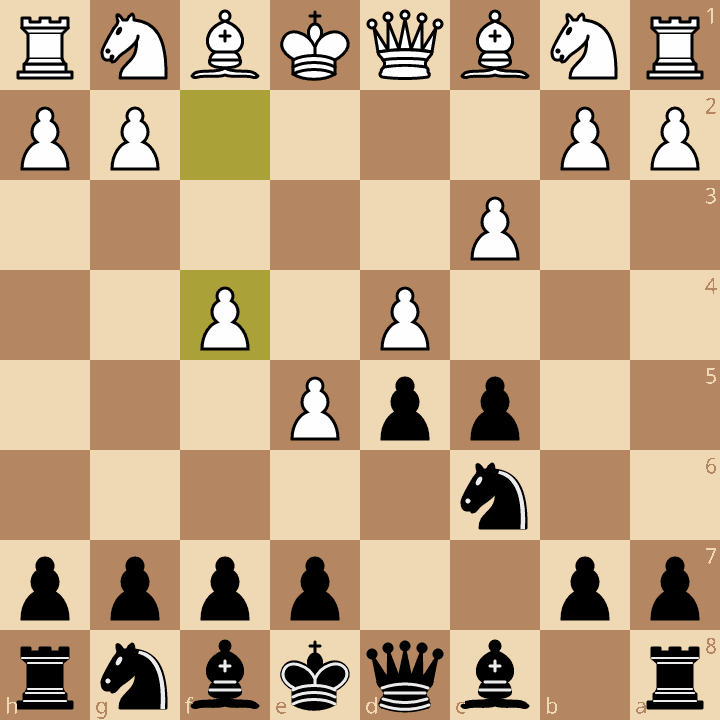

I immediately thought of anchoring bias when I was reviewing this game afterward. I had played Bf5 based on my knowledge of the move from another line in the same opening. But the problem is, in that line, White hasn’t taken the pawn on c5, so Black has more time to develop normally and pressure the backward pawn left by the trade on d4.

In this line, the one I got in my club game, the dynamic is totally different. White is up a pawn, and he’s gained queenside space to boot. It’s actually quite a good line for White, with the engine evaluating a 0.6 edge — it’s one of the most aggressive and dangerous ways to meet the Caro-Kann. However, it isn’t that easy to play, what with the f4 push and allowing a central pawn to become a wing pawn.

The key for Black is to play aggressively on the kingside, winning back the pawn before White can defend it. If White prioritizes the defense of it, they risk falling behind in development and leaving their other pawns vulnerable. Black should respond to 5.f4 with 5…Nh6, setting up the Bg4 pin that Black would have wanted to play had the game preceded with 5.Nf3.

So… it isn’t exactly anchoring bias. I could’ve been biased by the anchor of knowing I wanted to play Bg4, leading me to play the correct move of Nh6 in order to facilitate it. Instead, we’re dealing with something slightly different here: my prep had backfired. Rather than responding to the move based on what it achieved over the board, I played something that I remembered from my prep even though it wasn’t relevant. My prep hadn’t just failed to serve me — it had worked against me.

Turns out, this is a pretty common psychological phenomenon. There are a few different ways you can think about it. A good starting point is the concept of the Illusion of Explanatory Depth, which the Decision Lab describes as “our belief that we understand more about the world than we actually do. It’s often not until we are asked to explain a concept that we come face to face with our limited understanding of it.” They provide the example of a toilet: most of us would say we understood how a toilet works, but if pressed to describe it in detail, we’d realize that we knew basically nothing about toilets, despite having used them our entire lives.

That perfectly describes my comprehension of the opening. I had a sense that I understood it, but if you had asked me to describe why I played Bf5 there, I would’ve come up short. Sure, I could’ve justified it by saying that I was playing a normal developing move, getting the bishop outside of the pawn chain. But if you had asked me how I planned to get the pawn back, I would’ve had to admit that I had no idea, and that Bf5 wouldn’t help me do it. I had merely latched on to a piece of information that was floating around in my brain without knowing why it was useful.

There are more studies of this phenomenon out there. One that really resonates refers to “Strong-but-Wrong Sequence Application.” By introducing new processing sequences that resembled familiar ones, experimenters noticed that performers would make errors without realizing it, and they’d do it just as fast as they made their correct responses — suggesting a certain level of confidence.

Another study was performed specifically on chess experts, and it discovered that they would opt for familiar but less-optimal solutions to problems over less familiar but more optimal approaches: “The presence of the non-optimal solution reduced experts' problem solving ability… to about that of players three standard deviations lower in skill level by the presence of the non-optimal solution. Inflexibility of thought induced by prior knowledge (i.e., the blocking effect of the familiar solution) was shown by experts.”

All of these studies loosely describe the Einstellung Effect: the tendency for people to try and solve problems using approaches that have worked for them in the past, even when there are better methods available. This is exactly what happened to me in the game: I opted for an approach from a line that I had played before and knew, rather than trying to figure out a novel way of meeting this fresh situation.

Experts know what they don’t know

The consequences of the Einstellung Effect are deadly: it “hinders one’s ability to enhance their creativity and problem-solving skills as they don’t consider other perspectives or options.” This is, obviously, terrible for chess players, since chess is, if nothing else, an exercise in reaching creative solutions to problems by considering all perspectives and options. But it doesn’t take a lot of imagination to see how this could play into many of the problems we face today. By assuming that we know the answer to questions and dilemmas we encounter based on what has worked for us in the past, we prevent ourselves from rising to meet the new challenge.

Interestingly, the study on chess players provides a fascinating caveat: “The more expert they were, the less prone they were to the effect.” To me, that doesn’t just suggest that experts are better at avoiding the Einstellung Effect: it suggests that an inherent part of becoming an expert is your ability to avoid the Einstellung Effect. To become an elite performer, you need to be able to meet every new problem with a fresh perspective, rather than being handcuffed to your prior knowledge. This reminds me of the quote from Socrates: “For I was conscious that I knew practically nothing...” You need to know what you don’t know as much as what you do know.

What’s most ironic about my game is that, after starting to play this challenging line, my opponent immediately screwed up. In response to my Bf3, he played Be3?. This move defends the c5 pawn… but it allows d4!, which wins back the c5 pawn and gains space and development for Black.2 But even though I already knew by this point that I was flying blind, I just played the Caro-Kann-esque move e6 rather than assessing the situation on the board and looking for better moves.3 The problem went beyond the initial error — it characterized my entire approach to the game.

The simple lesson here? When I realized I was out of my prep, I should’ve let go of it entirely, meeting the position with a fresh perspective. But that is, of course, hard. It requires energy and ingenuity. It means that all of the work I did before the game was useless.

Still, it’s what the game required of me — and it’s what life requires of us as well. It’s nice to think that we can just fall back on the preparation we did earlier, that we’ve somehow earned ourselves security against the future. But the truth is that, when the future becomes the present, the past doesn’t really matter: it’s all about what we do now. And that means being willing to change your mind.

This is, of course, a dumb way to think, inclining me toward a favorable view of my opponent when he hasn’t necessarily earned it. But alas, I am only human.

This should also serve as a reminder that, just because your opponent starts to play a strong line doesn’t mean they definitely know the whole thing. I can’t tell you the number of players I’ve gone up against now who open with some wild approach and then don’t seem to know the continuation. Of course, they’re usually teenagers, which… does seem like teenager behavior.

This also hints at one of the biggest challenges of opening prep: for it to really pay off, you need to do a lot of it. It’s not that you have to memorize a thousand lines, but you do need to have some familiarity with the most frequent structures and responses you’ll meet. Otherwise, you’ll encounter the situation that I found myself in, which is that, even when you’ve prepped the most common line, you’re still likely to face it in a minority of situations. Better to memorize 20 sequences of five moves than five sequences of 20 moves.

People highly overrate opening prep. I watch lower rated tournaments on Lichess broadcasts, around 2000 FIDE, and often people are out of book by move 13 at the latest.

I've been learning the Tal. A switch away from the Panov. And when people go c5, I just take and play a3 after Nc6. Doesn't matter how far they know that line. The game will diverge at some point in the next 10-12 moves. That's what I see in those tournaments as well. Which I take to mean having a superior strategic middlegame plan is far more important than trying to go move for move in the opening.

I play that early c5 line too. Best response to dxc is e6. Yes you close in the bishop but one of those two pawns will fall and Black is ok