In sports1, not all losses are created equally.

There are blowout losses, in which the outcome is more or less determined from the first second of competition — or even earlier. There are solid defeats, in which the chance of a comeback exists, but the contest is never that close. There are tight games, in which the result could go either way up until the end, when one side or the other manages to prevail.

And then there is a fourth kind. The heartbreakers. The choke jobs. The miracles, if you happen to be seeing them from the side of the winner.

It’s one of these losses that I experienced last week. And I’m going to spend the rest of this newsletter trying to tell you why that was, in fact, good.

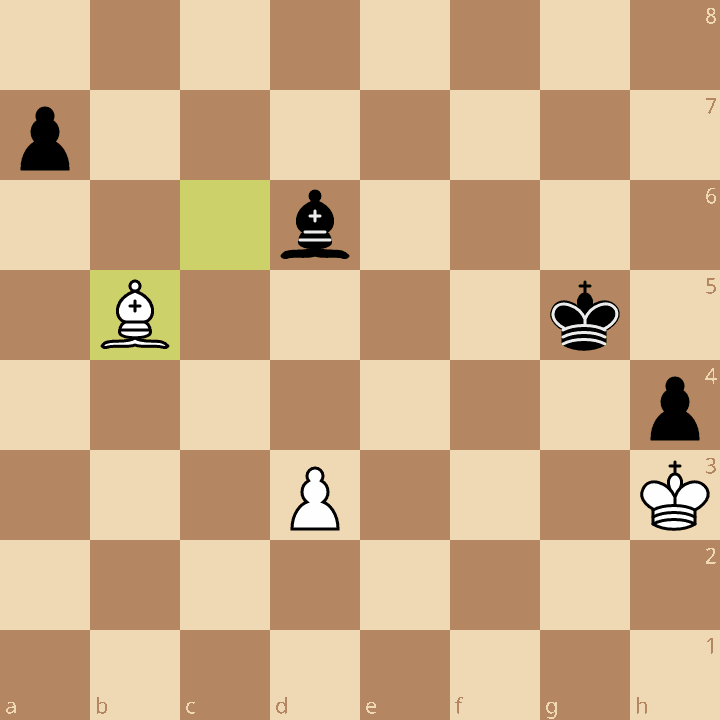

A Position.

What we’re looking at here is the 53rd move of my club game last week, our first in the new digs of the San Marino Masonic Lodge, where we relocated after the Eaton Fire burned down the Altadena Community Church. (The chairs are a major improvement.)

It was the first round of our latest tournament, and I had the White pieces against a pre-teen rated 1869 — a good 230 points above me. As I’ve written about before, I like these matchups: they make me feel like I have nothing to lose. Moreover, I get to test myself against strong competition.

I like them — until I get to a position like this. Now, an experienced chess player will be able to look at this board and immediately understand something: this is an opposite-colored bishops endgame, and these types of positions tend to end in a draw. The engine has it at 0.0. It isn’t quite mathematically drawn, but it’s pretty damn close. (Here’s a link to the chess.com analysis board if you want to play around with it.)

I knew this. I knew that, after an extremely tight three-hour struggle, I had obtained a drawable position against a much higher-rated player. But here was the problem: I didn’t know how to achieve the draw.

I haven’t put that much time into endgame studies. That knowledge tends to come in handy less often than tactics and middlegame strategy, and so, when choosing what to spend my limited study-time on, I usually opt for those categories instead of, for example, working my way through Silman’s Complete Endgame Course. (Guess where opposite-colored bishops endgames appear? The 1400-1599 chapter — i.e. the one I should have just completed, if I were following along with my rating.)

On top of this, I was facing a major time-deficit: my opponent had about 15 minutes more left on the clock than I did. All of a sudden, the dynamic of the game had changed. At first, I didn’t expect to draw or win. Now, I expected to draw — and any other outcome would represent a botched job.

I offered my opponent a draw. He declined, understanding, rightly, that there is a big difference between a theoretical draw and an actual draw. And then I proceeded to botch the job.

I’ll spare you the gory details, but the gist of what happened was that I traded off my bishop for his a-pawn, he hoovered up my c-pawn, and then, under intense time pressure, I mishandled my king, allowing his pawn to slip by.

After I resigned, my young opponent explained that if I had just put my king in the corner, on the h1 square, it would have been impossible for him to dislodge me, having the wrong-colored bishop for the queening square.

“I’m so lucky,” he said, seemingly without any awareness of how that might sound to me, the unlucky one.

I walked out into the San Marino night. It was 10 pm, and I’d just lost a three-hour-long game. My body had been shaking from the intense concentration, and my shoulder ached. I continued to shake slightly as I stood outside, contemplating the futility of existence in the light of chess endgames.

I did not sleep well that night.

A Lesson.

Let’s get something out of the way: obviously, losses are good learning experiences. That is basically the whole premise of this newsletter. I wrote about it very specifically two weeks ago.

But what about these kinds of losses? The heartbreakers, the choke-jobs, the near-misses? The ones that you end up replaying over and over in your mind, despite the all-too-obvious reality that, no matter how many times you move your king to h1 in your head, nothing’s going to change?

Do these losses have value? Or is this just the dark side of being passionate about something, the stuff that you have to put up with on the road toward improvement? Or, even worse, is this the type of thing that, given a long enough time-arc, eventually drives you insane? (Not that this has ever happened to a chess player.)

It’s not an easy thing to talk about, and not because it’s somehow off-limits or taboo. It’s just… weird. If you google “sports quotes about losing,” you’ll be hammered with the most remarkable succession of cliches and platitudes that you can possibly imagine. A fitting example is this one, from Muhammad Ali: “I am grateful for all my victories, but I am especially grateful for my losses, because they only made me work harder.” You don’t say.

Now, this isn’t untrue: it’s very true. But it isn’t exactly a revelation. Yeah, obviously, if you lose, you need to bounce back, you need to learn from it, you need to work harder. The bigger and more interesting question, I think, is what you do with that feeling: the disappointment, the regret, the self-recrimination. The pain.2

For example: after Josh Allen lost to the Chiefs once again, he said, “To be the champs, you've got to beat the champs, and we didn't do that tonight.” Again… sure. Hard to argue with that. But I want to know what Josh Allen does to convince himself that he can beat the champs. That, the next time he faces Patrick Mahomes and the Chiefs in the playoffs, it won’t just go the same way.

If there is any difference between champions and the talented players who never quite make it — if that gap isn’t just comprised of luck — then it’s probably the ability to do this.

There are many techniques that sports psychologists offer for how to go about steeling yourself after a loss, and in my experience, they do work. The psychologist Blakely Low-Scott suggests a few approaches drawn from Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, including “meeting the pain of losing with mindfulness,” “granting yourself the compassion you’d show a teammate or friend,” and “prioritizing the most ‘workable’ thoughts about a loss.” It is definitely true that if you can take a step back and think, “Would I say this to someone else?”, you’ll often realize that you’re being way too hard on yourself.

But I have another suggestion. Don’t tolerate the pain, or ignore it, or react to it intelligently. Love it — see it as a valuable, necessary part of the journey.

This might sound glib, or like I’m saying something that is impossible to actually practice — the sports-performance equivalent of the Stoic injunction to just like, not care about anything that isn’t fully in your control. And I will admit that I don’t exclusively love the pain. I am human. I would much rather have won last week, and in the aftermath of my loss, I’ve felt annoyed, disappointed, and regretful at various points.

However, like that Stoic advice — as annoying as it is — loving the pain might be hard to do to perfection, but it is possible. I believe this process has two steps.

First, you must appreciate a few different things about the loss, aside from what it teaches you. For example, I performed extremely well — I played a kid who has been rated in the 1900s to what was effectively a draw. That’s true regardless of the result.

Also, the loss was definitely funnier than a win would have been. Had I won, the kid wouldn’t have said to me afterward how lucky he was, and I wouldn’t have had that moment of standing outside the Masonic Lodge after three hours of focus, feeling like I’d just been run over by a truck. This is a better story than if I drew the game. It just is.

But to understand the second, more important step, it’s helpful to look at the aforementioned Josh Allen’s bête noire, the Kansas City Chiefs. This version of the Chiefs has had a run of success nearly unmatched in professional sports. Patrick Mahomes has been to the AFC championship in all seven seasons of his time as a starting quarterback. And yet, they consistently lean into the narrative that they are underdogs, that nobody believes in them. Which is… very clearly not true, no matter what the betting odds are.

Do you know why they do this? Because they have to. Losing is such an essential part of having a winning mentality that, if you never lost, you have to pretend that you did. You have to convince yourself that nobody believed in you, that you’re the underdog, that you’re constantly defying expectations. Tom Brady did this in 2019, after he’d already become the most decorated quarterback of all time. Sure, Tom Brady was an underdog in 2000. But twenty years later, he was only an underdog in his own mind.

It’s more than just motivational. It’s archetypal. There’s a reason why, at the end of every second act of every movie, you get the “all is lost” moment, Joseph Campbell’s “abyss.” Without it, you don’t have a satisfying shape to your story.

It turns out that our careers as athletes or chess players or whatever other hobby we might pursue tend to exist insofar as we give them a narrative. They are stories that we tell ourselves about ourselves, that we’ve created within the context of the larger chaos and unboundedness of our lives in order to give said lives some manageable, microcosmic pattern.

Does it matter at all that I lost a chess game last Monday? Of course not. But within the narrative of Kevin Lincoln the Chess Player, does it matter? It sure does. And just like the low point in an episode of television, I can enjoy it as a spectator, as Kevin Lincoln the person, knowing that it’s part of the experience, part of the story, and that next week, in the next episode, I will have the chance to achieve a different result.

This is the essential point. Losses are interesting. They’re meaningful events that, within the safe and structured context of a hobby, provide you the chance to challenge and grow emotionally without really having to risk anything, so long as you don’t over-invest yourself. And if you are over-investing yourself — if you can’t, at least to some extent, love the loss — then they’ll show you that you’re doing so.

On a more practical note: you will lose. This is inevitable. You might as well find a way to enjoy them, to appreciate these results not only as lessons, but as fundamental qualities of the experience in their own right.3

Let’s face it: in our dreams, in our fantasies, we only want to win. But a story that only involves winning is a boring story. It’s a villain’s story, and the only satisfying end to such a story is a loss, anyway.

So next time you suffer a heartbreaker, a nail-biter, one of those losses that punches you right in the stomach, remember: you’re a survivor. You’re an underdog.

Nobody believes in you.

And keep reminding yourself of that until you win.

For the purposes of this newsletter, at least, chess is a sport.

I’m using this word sort of in jest. Obviously, the situation I’m describing pales in comparison to real pain. But I do think that anyone who has competed passionately in a pursuit they care about understands what I mean when I say “pain” here.

You might suggest that this whole newsletter is just me trying to do this — to alchemize a loss I suffered into something meaningful. To which I would respond: exactly.