I Finally Took a Risk. Did It Pay Off?

Or should I go back to playing for draws?

Hello! Once again this week, a little housekeeping before we dive in:

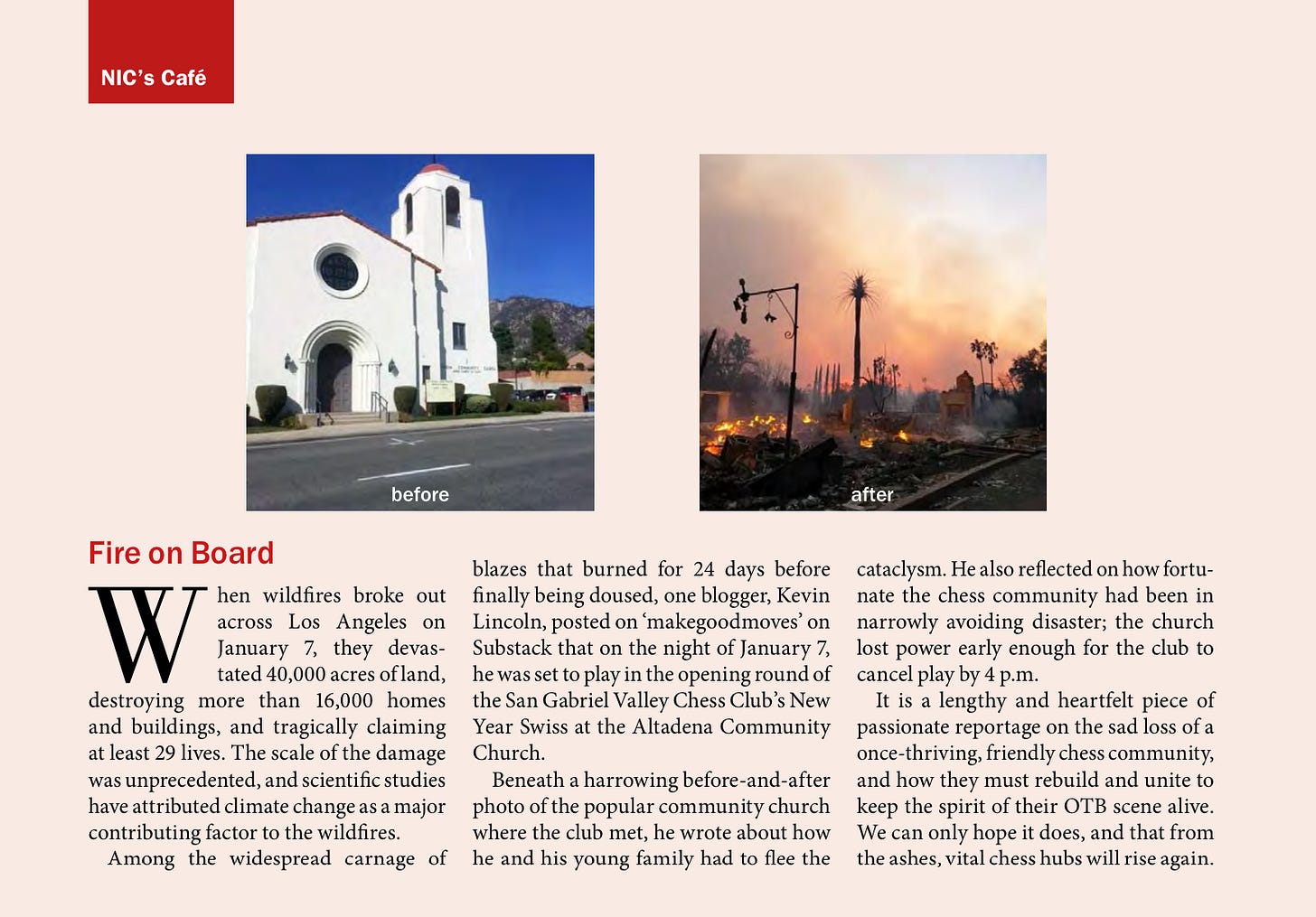

New in Chess, the great Dutch chess magazine, highlighted my piece “On Chess Clubs and Wildfires”! I’ve heard from a few folks at my club that they discovered it through New in Chess, and I’m glad that the magazine is shining a light both on the club itself and the larger importance of OTB.

And now, back to business. I’m happy to report that this week, I FINALLY took a risk. But did it pay off? Or did it blow up in my face? Or, synthesis alert, did it blow up in my face AND pay off? Here at Good Moves, we live in the gray area. Let’s dive in.

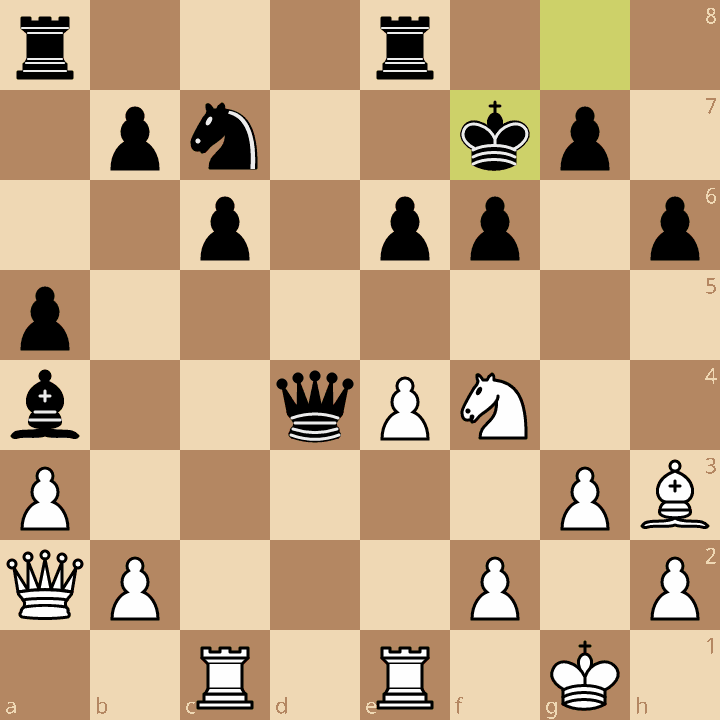

A Position.

Move 27, White to play. I’d invite all chess players reading this to spend a little time with this position, as if it were a puzzle. I think it’s one of the better examples of said category that I’ve found from my games, as it has a very clear solution, but it isn’t simple. I’d actually be curious to hear, especially from the higher-rated players reading the newsletter, what difficulty they think this position clocks in at.

Anyway: I’m up against a teenager rated 1865 — a good 200 points above me. I’ve never played him before. Multiple times during the game, he gets up and sort of dances after he makes a move, which is… interesting. I can’t tell if this means he thinks he made a good move or if he’s just nervous. Either way: gotta stay focused! At least he’s not coughing!

It’s been a hard-fought contest — for the first 16 moves or so, it’s pretty even. But then, on move 17, he makes a mistake, playing f6 to kick my knight from e5. It’s a badly weakening move for his pawn structure, and all of a sudden, I have a target. My game from then on is devoted to putting pressure on the weak e6 pawn, working the various tactics that exist around that focal point. He almost manages to tie up my queen in the corner there, but plays Ba4 on move 23 instead of the strong Bc4, which would have interrupted the crucial pin that I have going.

His most recent move, Kf7, appears to strengthen the defense of the pawn — but in reality, it ignores the actual threat I have on the board. I want to put my rook on the open d-file with a tempo on his queen, threatening Rd7 check — where I have a double attack against his king and knight. To do that, I need to kick the bishop from a4. And I can do that: I just have to play b3. Yes, it blocks my queen’s pin on the king, but one step at a time, right?

I play b3. He plays Bb4. I play Rcd1. And then he plays Qc5. This is not the best move, but to spare the reader too many variations, we’ll do the deep dive in a video, which comes later in the piece. I’m also going to do a bit more chess writing than usual here, so if you’re more interested in the performance insights, just skip ahead to the Takeaway section.

I play Rd7+, and he blocks it, as expected, with Re7. Here’s where we arrive:

This is a fascinating position — maybe the most fascinating I’ve ever reached over the board. There’s so much going on: I have quite a bit of pressure on the e6 pawn, but not enough that I can just outright take it. My rook is hanging, so I need to do something with it. And my queen, for now, is blocked. But I have that intuitive feeling, the Spidey Sense that all chess players are familiar with, that I’ve got something in this position, something really good. I just don’t know what it is — and, to make matters worse, I’ve only got 10 minutes on the clock, whereas my opponent has, like, 40.

Regular readers might notice that this is starting to become a pattern for me: I’ve been down on the clock quite often lately. Partly, this is because I’ve wanted to prioritize calculation and risk-taking, and so I’ve been giving myself more time to find the best moves in any given position. But it’s starting to become a liability — it’s causing me to rush through the most crucial positions. I’m going to have to pay attention to it in the future. I shouldn’t be routinely falling behind by 30 minutes or more.

As a result, I don’t have quite as much time as I would like to calculate in this absolutely pivotal moment. But the thing I do notice is that the Black knight and rook are both covering e6. If I take the knight with the rook, then when the Black rook takes back, e6 will be under-defended. This is called eliminating the defense — the Black rook has to defend both the knight and the pawn, and it can’t do both. It’s overloaded.

But I’m not quite sure about the follow-up. I see that Nxe6 would create a fork against the rook and the queen. Does that work? Maybe? This is the point where I need to think about Black’s follow-up… but the clock is ticking.

Meanwhile, I have another option: I could play Red1, solidifying my dominance of the d-file. But this would be wasting a crucial tempo that Black could use to defend himself. And, on top of that, it’s boring. Safe. Exactly the kind of move I’m trying not to play when I’ve got a better option on the board.

Screw it: I said I was going to take a risk. Let’s take a risk. I play Rxc7.

A Takeaway.

I’m currently reading The Courage to Create, an excellent book by the existential psychologist Rollo May. In a subchapter called “One Paradox of Courage,” May writes:

A curious paradox characteristic of every kind of courage here confronts us. It is the seeming contradiction that we must be fully committed, but we must also be aware at the same time that we might possibly be wrong. This dialectic relationship between conviction and doubt is characteristic of the highest types of courage, and gives the lie to the simplistic definitions that identify courage with mere growth.

People who claim to be absolutely convinced that their stand is the only right one are dangerous. Such conviction is the essence not only of dogmatism, but of its more destructive cousin, fanaticism. It blocks off the user from learning new truth, and it is a dead giveaway of unconscious doubt. The person then has to double his or her protests in order to quiet not only the opposition but his or her own unconscious doubts as well… In contrast to the fanatic who has stockaded himself against new truth, the person with the courage to believe and at the same time to admit his doubts is flexible and open to new learning…

The relationship between commitment and doubt is by no means an antagonistic one. Commitment is healthiest when it is not without doubt, but in spite of doubt. To believe fully and at the same moment to have doubts is not at all a contradiction: it presupposes a greater respect for truth, an awareness that truth always goes beyond anything that can be said or done at any given moment.

You said it, Rollo. I’ve always been a big believer in the ol’ Scott Fitzgerald chestnut, “The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function.”1 It doesn’t take a tremendous amount of imagination to appreciate the relevance of such a thought in today’s world, but what I love about The Courage to Create is that May takes this notion and applies it directly to the creative act.

He stresses the importance of the “encounter” as the place where creativity really happens; it’s all about manifesting the energy of creativity in and through the world, rather than any question of talent or ability or quality. You can be creative without having to be certain of the value of your creative output; in fact, your doubt is probably good, insofar as it means you have an authentic relationship with the “truth,” which is that it might not be good — or, to be put it more in the language of creativity, other people might not like it, whether it’s good or not.2 It also means that you have to muster the courage to overcome said doubt and ACT, in spite of the voice in your head screaming at you not to.

Back to our chess game. Rxc7 is not just a good move — it’s a “brilliant” move, according to the engine, because it sacrifices material and leads to a winning follow-up if the material is taken. Brilliant moves are hard to come by; I’ve only played one or two others over the board.

It appears, then, that my desire to become risk-seeking has been rewarded; that my killer instinct has broken out, Mamba-like, from the brittle egg of my patzer-dom. Now I am become Magnus, destroyer of kings. Etcetera etcetera.

Except, except: what did I do next? Next, I played… Nxe6. Which is bad. Wrong. A mistake. Worth a 7.5 — 7.5!!! — eval swing. In the space of a move, I went from clearly winning to probably losing. Black has the resource Qc3, which defuses the fork by threatening to take the rook with check. White has merely given away material, with nothing meaningful to show for it. Sure enough, my game disintegrated from there, and I lost.

Here’s a video to walk you through exactly what went down — as always, skip if you’re here for the performance stuff rather than the chess stuff. It’s on the longer side, but there was a lot in this game to talk about!

So. I took a risk. And it… almost paid off? But then it didn’t.

If I hadn’t taken that risk, if I had doubled my rooks, I almost certainly would have been better off. But. BUT. But. Sacrificing the rook was so cool. And, moreover, it was right. And, mostover, it was winning. The fact that I didn’t find the right follow-up didn’t mean that taking the risk was bad. Now, would it have been better had I seen the succeeding move and unfurled a beautiful winning sequence, vanquishing the higher-rated player and earning myself a huge ratings leap as well as the knowledge that I was a blessed son of Caissa? Of course. But what I learned by taking this risk was that I can trust my intuition. When my Spidey Sense is tingling, I should listen to it. Does that mean I should play every sacrifice I consider? Absolutely not. I should play some of them, though, because some of them, like this one, will be right.

This is why I quoted May above. In this case, I fully committed despite harboring some doubts, and it turned out that I was right to do so. I harnessed the courage to at least try to create something spectacular, rather than settling for the conservative move, drawing play, and the nagging awareness that I had once again passed up an opportunity to win.

For maybe the first time ever after a loss, driving home, I was stoked. It felt like I had grown up as a chess player, like I had unlocked a new skill in a video game. I can find these combinations over the board. I didn’t this time. But I have the capacity. This strikes me as far more valuable to my growth than digging in and scrabbling for another half-point draw.

Now, should I slow down next time, not rush my follow-up even if I am struggling on the clock, and make sure I understand what my sacrifice is accomplishing? Yes, definitely. It’s easier to appreciate that once you have some real-world evidence of why and how it matters, though. And now I do.

Later in The Courage to Create, May writes, “What the artist or creative scientist feels is not anxiety or fear, it is joy. I use the word in contrast to happiness or pleasure. The artist, at the moment of creating, does not experience gratification or satisfaction. Rather, it is joy, joy defined as the emotion that goes with heightened consciousness, the mood that accompanies the experience of actualizing one’s own potentialities.”

Bingo. Actualizing one’s own potentialities feels awesome — way better than accepting a draw offer in a winning position, or waiting for my opponent to dictate the game. I can’t wait to try and do it again. This is why I play chess.

Ephemera.

Before I go, I wanted to share this write-up of the Women’s World Championship Game 2 by Dennis Monokroussos over at the Chess Mind. Dennis makes a point that spoke directly to me, since I feel like I’m often guilty of succumbing to this temptation, and have done it in this very newsletter — looking at the engine, seeing a number, and accepting that number as objective reality. Dennis writes:

The first game of the Women’s World Championship match between Ju Wenjun and her challenger (and predecessors) Tan Zhongyi was a peaceful draw, and game 2 seemed headed in that direction as well. The champion didn’t have too much trouble on the Black side of a Four Knights English with 4.g3, and while Tan enjoyed a mild initiative throughout the single-rook ending that resulted after 31.Rxa7 seemed a sure draw.

Instructively, it wasn’t. Drawn, yes, but as years of Magnus Carlsen victories from “drawn” endgames have shown us (or should have, if we were paying attention), we’re all far more capable of losing allegedly equal positions than we’d like to admit. One culprit in all of this is the engine, of course. Used properly it’s a great teaching tool, but one of its limitations at the moment is that it will evaluate a wide range of positions with the infamous “0.00” score. The problem is that not all zeroes are relevantly equivalent. Broadly speaking, there are three kinds or types of moves that can result in a 0.00 eval: (1) There are moves that force the draw or at least bring the draw closer and make it easier to achieve. (2) Moves that keep the game drawn but don’t make progress, generally making it somewhat harder to achieve. (3) Moves that don’t “officially” spoil the draw, but force one to play like a superhero to squeeze it out by the skin of one’s teeth. The naive engine-user keeps seeing all those triple-zeroes and thinks the loser blundered when the zeroes are finally gone, but much more often the problem was a series of Type 2 moves, often with a Type 3 move at the end, followed by the inevitable failure to find all the perfect moves at the last stage.

Remember, people: humans aren’t AI.

Also: I just finished Wolf Hall. You heard it here first3, folks: Wolf Hall is great.

From his Esquire essay “The Crack-Up.”

I don’t really feel like defining “truth” here — it seems beyond the scope of a newsletter about chess. But anyone who wants to have a philosophical debate about it, whether they’re a Bishop Berkeley-ian idealist or a materialist in the Daniel Dennett mode, is more than welcome to start one in the comments!

Excellent write up. I am grateful to be reminded of Rollo May!

Congrats on the NIC mention, and on going down swinging!