Can You Develop a Killer Instinct?

Or are Kobes born, not made?

It’s official: I have a nemesis. And she’s 13.

My opponent last week was someone I had faced twice before already, and who I’d written about once. At 1838, she out-rates me by over 200 points. She’s very good, and she’s the first person at my club who I’ve faced three times, which is what makes her my nemesis.1 (That, and the fact that she keeps beating me.)

But aside from our legendary, Tobacco Road-level rivalry, our last game was interesting for a more prosaic reason: it highlighted what seems to be one of my more glaring weaknesses at the moment. Let’s dive in.

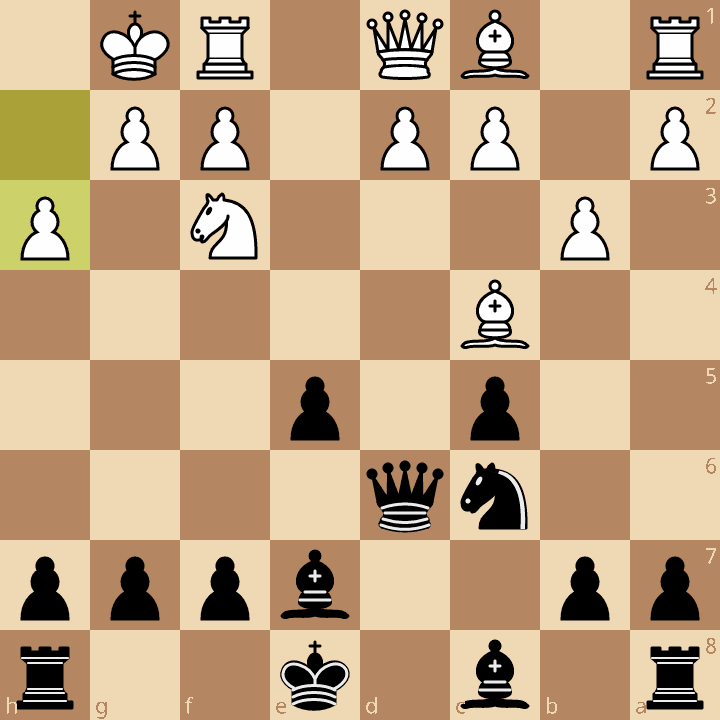

A Position.

It’s move 10, Black to play. Unlike my last couple of games, I’ve managed to get a very strong position out of the opening. I’m dominating the center, and my pieces are far more active than White’s. But White’s dark-squared bishop is headed to b2, where it will target my e5 pawn, so it won’t be long before White has pressure of their own.

What do I do with this advantage — with this temporary edge? I’ve noticed that I could push e4, deflecting the knight. But after h3, I figure that the knight will just head to h2, where it can relocate to g4 eventually. That doesn’t seem that bad.

So instead of forcing the issue. I play it safe. I castle. I develop and consolidate, operating under the impression that I will continue to hold the reins. You can’t go wrong with making solid, fundamental moves, right?

WRONG.

One of the things that makes chess so fascinating is that one move can completely shift the balance of a game. Unlike any competition in which points are aggregated over time — which is most of them — you could be absolutely dominating in chess and then lose a move later. In that sense, it’s more like martial arts or boxing than most other sports: there’s always the chance of a knockout, of a total shift in momentum irrespective of points scored and leads accumulated.

What does that mean for players? It means that, when you have an advantage, you need to press it. You can’t just sit back and assume that you’ll have a chance to make good later on. It’s always now or never. Even the word “temporary” suggests this: it contains within it the idea of a “tempo,” a crucial concept in chess that has to do with who is in control of game-time.

Now, that doesn’t mean it’s always right to attack, or to go for checkmate — it just means that it’s always right to do something that strengthens your position while exploiting your opponents’ weaknesses. General “good moves” are not good enough.

Back to the game. We’ve already established that I have a superior position. And, as Bobby Fischer says, “Tactics flow from a superior position.” If you want to attack, and you’re not sure how to do it, then playing with tactics in mind is generally a good principle. It’s not even that hard to find where the tactic exists here: if I put my queen on g6, I’m pinning the g2 pawn to the king. Bxh6 becomes possible, and e4 makes a bad situation worse. White has to react, and they don’t have time to concretize a plan around attacking the e5 pawn. I’m now completely dictating the flow of the game.

As is typical of this newsletter, we’re asking two questions here. We’re asking, first of all, what happened on the board. And then we’re asking what happened with my mental approach. As usual, these two ideas are directly connected: by not understanding that I had to force the issue of my advantage, I didn’t look hard enough for the aggressive moves. And because I didn’t look hard enough for the aggressive moves, it was easy for me to opt for the passive move that seemed like a safe choice.

I feel like I say this every week — but if I’m going to beat players who are in the 1800s, then I need to play more aggressively. If I let them control the game, then I will lose nine times out of ten, and the tenth time I’ll manage to hang on for a draw.

But it’s one thing to say I need to be more aggressive. It’s another thing to actually… be more aggressive. Is that even possible? Can you learn aggression? Or is a killer instinct just that — an instinct? To put it another way: are Kobe Bryants born, or can they be made?

Last week, we talked about prospect theory and risk aversion. This question is essentially an extension of that idea. In that piece, I asked whether it was better to risk a known result for a better but unknown one. This week, I’m saying that I know I want to become more risk-seeking my play — the issue now becomes, how do I do that?

When you dive into this, you discover a lot of suggestions: change your mindset around risk. Raise your risk ceiling. Normalize failure. All of these felt a bit vague to me. I was curious to see if there was a more paradigm-shifting way of conceptualizing the problem. Rather than changing my attitude toward risk, how could I change my attitude toward chess as a whole in order to become more risk-seeking as a downstream effect?

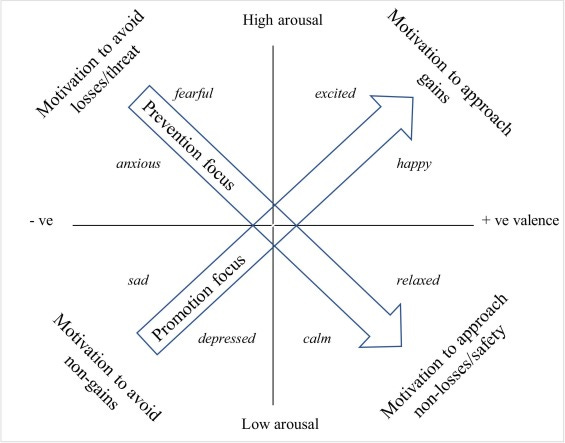

Over the course of my research, I discovered a concept I wasn’t familiar with: Regulatory Focus Theory. Created by the Columbia professor E. Tory Higgins, RFT suggests that people tend to pursue goals in two different ways: either promotion-focused or prevention-focused.

A person operating from a promotion-focused orientation wants to make gains, grow, and approach an ideal. A person operating from a prevention-focused orientation seeks security, the avoidance of losses, and the fulfillment of duty. Either is capable of fulfilling their goal, but promotion-focused competitors tend to be more risk-seeking, and their prevention-focused counterparts more risk-averse.

I find this model… uncannily accurate as a framework of my approach to chess.

I’ve said in the past that I like to play higher-rated players. I think many people might see this as a promotion-focused orientation: I don’t mind losing in order to achieve my goals of getting better and growing as a player. And maybe, to some extent, it is. But it could also be seen as prevention-focused: if I lose to a higher-rated player, I sustain smaller ratings losses than if I lose to a lower-rated player.

It’s funny: if you look at my record as a competitive chess player, it presents a different picture than my rating. I’m 7-5-11 in 23 games so far. That means I’ve lost nearly as much as I’ve won and drawn combined. I’m getting used to losing, and I’ve come to understand that I can lose to good players and still maintain a respectable rating, as long as I notch enough draws and the occasional win against said players — I can take a prevention-focused approach and still “succeed.”

But what do I want out of chess? Is it really to protect my rating? Or is it to push the upper limits of what I’m capable of over the board?

To wax philosophical for a moment: a great chess move shares qualities with a work of art. It’s creative, ingenious, and unexpected; it both subverts and elevates form. In a very basic sense, it can be beautiful, but it can also be clever, provocative, or insane. This is why I love chess. It’s a means of expression bounded within a fascinating and esoteric system of rules, knowledge, and technique. It combines everything I love most about the world: beauty, creativity, structure, learning, and depth.

All of which is to say that, if I’m going to honor why I really like chess, then I should try to shift toward a promotion-focused orientation. Telling myself to take more risks isn’t good enough; it won’t resonate on an emotional level. Instead, I should try to find and then play the beautiful, creative, and insane move. That’s how I’ll make myself more risk-seeking — if I can align risks with why I’m doing it in the first place. If I can shift the focus from my rating to my play.

Let’s go back to the Kobe example. Nobody could tell you exactly why he trained like such a psychopath. But clearly, there was more to it than just wanting to destroy everyone he faced. He was chasing an ideal. He was about as promotion-focused as any athlete ever. This is why he was able to practice and train and drill like he did: he knew that it was all for a greater purpose.

You might say, “Kevin, it’s simple: if you want to be like Kobe, you need to train like Kobe.” That’s what made him so great, not his mindset. But the only way to train like Kobe — the only way to sustain that kind of workload and dedication when you really don’t have to — is to create a mindset in which every ounce of practice, every second of commitment, serves as a stone placed in a larger structure. You’re working toward your ideal. You’re not just trying to stave off failure.

My goal for next week is to report back to you good people with a move that fulfills this mandate — even if it fails miserably. Stay tuned!

At the risk of stating the obvious, I’m joking here. Obviously I don’t think of a 13-year-old as my nemesis. She’s just way better than me.

I think a big part of what you're writing about here is what Jonathan Rowson calls "sensitivity" - the idea that as you get stronger you become more aware of potential critical moments - it's the remedy to the sin of "blinking" in his Seven Deadly Chess Sins book.

There's also a memorable story in Mark Dvoretsky's book Attack and Defense in which he's playing badly and is pissed off so he tells himself that he's going to think for five minutes on his next move to get back on track. His opponent attacks a piece, so Dvoretsky thinks that the time will be wasted, since his next move is to obviously move the attacked piece, but he's committed to the five minute think, and it turns out that there's a brilliant piece sac instead - he tricked himself into being sensitive to the moment.

Regulatory Focus Theory both makes me feel seen and attacked!! My competitive powetlifting career motivated me to study performance psychology/philosophy and RFT so neatly summarizes so much of what I've learned, and in a uniquely insightful way. Thanks Kevin for writing about this!