Last week, the great chess god Caissa heard my laments about constantly getting beaten by a 13-year-old girl and, putting to good use that fine sense of humor for which she is so well known and loved, decided to pair me with a nine year-old girl. This nine-year-old was rated 1699, or about 65 points higher than me. You can imagine why so many adults like playing at the ALTO tournaments, where only players 21 years of age or older are allowed. Significantly less risk of fatal damage to the psyche.

But despite all of the ingredients for ego-death being present, I managed to fight my way into a pawn-up endgame — where I faced one of the great dilemmas of not just chess improvement, but of learning anything ever.

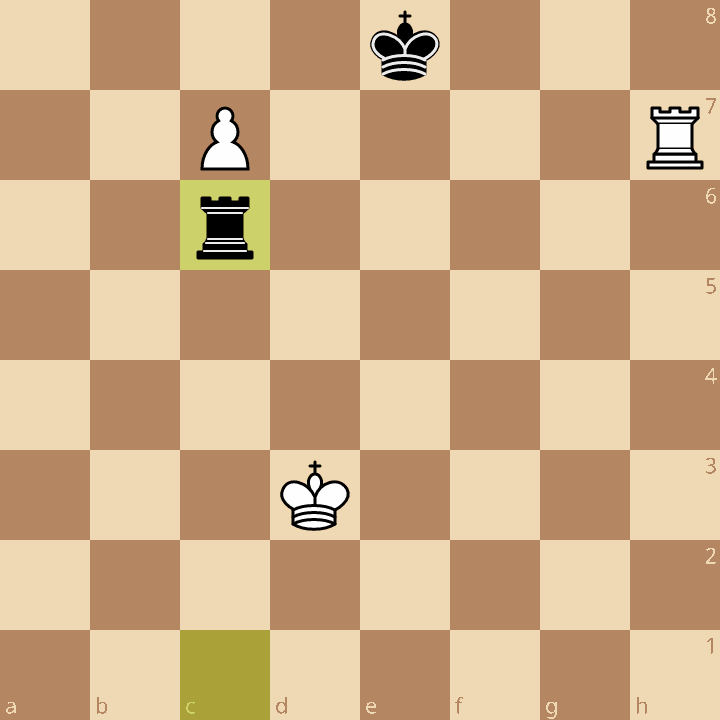

A Position.

The time control at my club is 90 minutes per player, with a five-second delay on each move before the clock starts running. When we reached this position on move 60, I had less than a few minutes left. It’s hard to describe the feeling of starting a game with 90 minutes on the clock and then realizing you’re down to your last few seconds. I would imagine it’s a little like having millions of dollars and then looking at your bank account to discover that you have, like, $12.

I mention this because I want to allow for the possibility that maybe, just maybe, if I’d had 15 or 20 minutes on the clock, I could’ve figured out how to win here. But I don’t think so. The truth is that I’d reached the kind of endgame situation where you just have to know what to do. It’s too complicated to puzzle out over the board — but if you understand the situation and the techniques that can be applied here, it’s an easy win.

I’d ended up in a classic Lucena position. (Or it would have led to a Lucena position if I played it correctly.) Jeremy Silman calls it “the sacred key to all rook endings” and “one of those bits of chess knowledge that every serious player must possess.” (Oof.)

I’ve recorded a short video to walk you through it, not only so that you’ll have the knowledge to avoid losing in any Lucena position you might reach in the future, but also so you can understand, if you aren’t a chess player, just how much these kinds of positions are a matter of knowing what to do rather than solving it in real time.

Of course, I couldn’t figure it out on my own, and, with less than a minute on the clock, I felt that I had no choice but to trade into a drawn endgame. I still got the draw, which means points for my rating, but I’d given up what should’ve been an easy win, if only I ‘d known what to do.

This leads to an obvious and fascinating question. For the rest of my chess career, I will never forget how to play the Lucena position. This is because I learned it the hard way — at the cost of real stakes. I’ve written about this before, when I lost what should’ve been a drawn opposite-colored bishop endgame.

At that time, my conclusion had been that I should grow to love the pain — that I should appreciate the opportunity to learn lessons this resoundingly, with the help of such emotional signifiers. But as such lessons add up, I can’t help but wonder… is there a way to learn some of them in a way that is less hard, but still resonant? That allows me to win or draw some of these games that I’m otherwise drawing or losing, and shifts the burden of my learning away from my OTB games, and creating fewer nights where I lay in bed, replaying the move in my head over and over?

As I was beginning to ponder this question, I saw that Dr. Nick Vasquez wrote about a similar subject over at his great Substack, Chess in Small Doses.

As some of you know, I’m a practicing Emergency Physician. The advice I’m giving you today is rooted in my experience as a chess player, a doctor, and a teacher of resident physicians. One huge challenge in medicine is that there is just so much to know. We have to learn a large amount of basic and specific knowledge in order to practice at a high level. It takes years in the best circumstances, but still gaps often remain. We have a saying that “The eye cannot see what the mind does not hold.” After 20 years of practice I believe that mastery occurs when you have both your senses attuned and connected to your book knowledge. This I believe works for both chess and medicine. More often than not, we play with the eye we have but miss the fact that we’re missing things.

Just like in medicine, chess players suffer the continual challenge of too much information. No one has a lack of access to information or chess knowledge anymore, we have a deluge of it. In our lives, information is presented to us every day in multiple ways. This excess leads to a strange sort of scarcity in our attention. We are forced to decide if we care enough to pay attention to it.

This is a very clear summary of the problem I’m describing. I had been told before that the Lucena position was important. But I wouldn’t come to care about it until it was too late, so I wouldn’t learn it until it was too late, at least for that game.

Here’s Nick’s conclusion for how to respond to this dilemma:

Our brains when overwhelmed just automatically filter out what doesn’t seem relevant to us. The real key to gaining and retaining knowledge these days is finding why it is relevant for you. In other words, finding out why you should care enough to spend time learning and encoding it. This was the entire point of the book Start with Why by Simon Sinek. No one cares until they know why something matters to them personally. Relevancy is the key.

Where do we get that in chess? Where can we find what is relevant to us? I’ve written this before, but I believe we find it in our losses and our mistakes. If we can tolerate failure and understand it’s just temporary, we can turn it into a great gain for us. Losing at chess has such a personal feel of failure it is very hard for people. Critically, losing shows us what our eye does not see. It’s the best form of reality testing out there. It’s only a loss or a failure if we fail to learn from it.

I totally agree with this; I’ve made similar points before. But it also reinforced the question I had above. Is there a way to do this without losing? Or, at least, losing the games that are most important to me, i.e. my rated club games — the games whose importance makes them the ones most capable of teaching lessons in the first place?

To answer this question, it’s first worth reflecting on what some things are that we know, from research, help people learn. There’s spaced repetition. There’s interleaving different skills and concepts versus repetitively drilling the same task over and over. There’s getting a coach or a cohort to help support you. These all work! You should do them!

As far as my game goes, I already use spaced repetition on Chessable to learn openings. (As Nate Solon points out — you need to actually do the spaced repetition. Many people are shocked by this. Unfortunately, learning stuff is hard!) And I definitely want to get a coach at some point. (If you’re reading this and are a coach or have a coach you like… feel free to reach out!)

As far as interleaving, this is why I think that playing games is so valuable. There is a big difference between finding a tactic when you know it’s there and finding a tactic when you don’t know it’s there; they require a totally different way of comprehending the board. Same goes for learning a concept. For example, I’m currently working my way through How to Reassess Your Chess. If Silman is writing about superior minor pieces, it’s one thing to read that information and comprehend it, but it’s a very different thing to actually use it in one of my own games.

There’s solid research into the idea that, if you want to perform well in a certain type of situation — say, a chess game, or piano concert, or a BJJ match — you need to practice in scenarios that resemble it, allowing for “perception-action coupling,” which is a fancy way of saying that you know how to apply the technical skills of whatever you do to the specific competitive environment you hope to utilize them in, not just in the vacuum of drills or exercises.

But there is, also, a reason to drill tactics or study concepts outside of playing games: because you’re aware that you’re studying tactics or learning concepts, you’re conscious of the context necessary to find and implement them. Compare this to the ease of playing games, particularly online, and attaching the meaning solely to the outcome, i.e. did your rating go up or down, rather than the details of the play, which become pure noise. If Silman walks me through a game and says, “This is why the knight is superior to the bishop here,” I’m going to understand it; if I’m drilling discovered attacks and I solve a puzzle, I’m going to register that as information about discovered attacks. On the other hand, if I play a game of my own and the opponent’s knight is superior to my bishop but I never identify that, or if there’s a discovered attack but I miss it, then it has no value. I will forget about that game within hours, if not minutes.

Herein lies the most important element of what I’m circling: in order to effectively learn, you have to find ways to create meaning around the material. That’s why OTB games are such great teaching devices: they have huge amounts of meaning. It’s also why deliberate practice works: “Practice activities are seldom, if ever, characterized by mere replication or repetition of movement patterns or drills without a progressively more challenging goal in mind. Such orientation to practice helps them resist or delay the automaticity that accompanies the more routine practice of cognitive and motor skills. In so doing, this enables the generation of increasingly elaborate and complex mental representations of tasks, factors that appear important foundations of subsequent expertise.”

So this leads me to a logical conclusion. The ideal situation is to play more games that have some level of meaning. At the same time, though, I don’t want these games to have the same amount of emotional stakes as my OTB games — I want them to hurt less.

This is essentially what Nick suggests as well:

I believe the best way to determine what’s important is to play and analyze your games. Looking for the simple mistakes or the common patterns. Once you start adding knowledge in these areas, your eye will see better what’s on the board. This is one of the surest ways to improve, but it’s also the hardest. None of us like failure. We prefer to study like we’re preparing for a test. Chess is more like a practice (more on that later). A never ending cycle of growth and learning. Doing this with intent and with purpose is, in my opinion, the best way to improve.

For myself, I’m going to take my own advice. Once I get to 20-30 rapid games I’ll stop to see what the issues are for me. Stay tuned.

I think this is basically spot-on, but here’s what I would add. I want to create an ongoing situation in which I’m studying widely — some tactics, some openings, some middlegame strategy — and then playing rapid games as a means of reinforcing my study. (Endgames, I think, are a useful and interesting exception: by training this way, I can, per Nick’s observation, let my play direct me toward endgame situations I need to learn more about. This works in part because endgames are so concrete: when you lose a rook-and-pawn endgame, you know you need to study rook-and-pawn endgames. It’s note quite as simple to understand the importance of, say, superior minor pieces until you’ve been introduced to the concept.)

Fortunately, I already play a lot of rapid games. Too many, in fact. I’ve been meaning to cut down on the number of games I play, which often happen in tilted moods in which I’m just trying to get back up to a certain rating number. Just look at my rapid rating chart over the last 90 days: it’s up and down, up and down, up and down, pinging between 1700 and 1625 or so. (I am currently, at this very moment, occupying my all-time high, though!)

There’s only one way to both cut down on the number of games I play and increase the number of meaningful games I play: I need to analyze every single game. And I don’t just mean, I’m going to run the Game Review and check the engine and nod and move on: I need to narrativize them, deriving some sort of meaning. I need to tell a story about each game, even if it’s just a sentence-long story.

I’ve been reading Anne-Laure Le Cunff’s fascinating book Tiny Experiments. One of her primary suggestions is to make “pacts” with yourself: contracts in which you pledge to do something for a set number of days. These pacts can’t be outcome-dependent, i.e. “I’m going to get to 1800 over the next 30 days” — that isn’t up to me. They need to be fully within my control.

So here’s a pact that I’m going to make, that you, dear read, can hold me to: for the next three months — so, until June 24, at least — I am going to analyze every single game I play according to Nate Solon’s OBIT method. I’ll compare the opening to my files and adjust them accordingly; I’ll look at my blunders according to the engine (and my mistakes, which I think are worth considering, too); I’ll isolate one element from the game that is “interesting,” meaning that I wasn’t sure what to do while playing (having to identify this in and of itself makes me think more consciously about how I’m playing); and, maybe most importantly, I’ll come up with a takeaway.

You can see how this might work: if I had reached the Lucena position in a rapid game I analyzed, then I might’ve learned how to play it before I reached the same spot in OTB. I would’ve learned, but in a less hard way than I did.

Now, I would love to share my file of analysis with all of you, but I think that would be giving away a bit too much. If you want to check how I’m doing, though, I WILL share my Google Sheet containing my takeaways from each game.

We’ll see how this goes over time — my biggest curiosity is whether a) it produces any insights that serve me in an OTB game, and b) if my Chess.com rating goes up by playing this way.

If you try anything similar in your own study, let me know!

Look forward to seeing what you learn!

Great post and I like the idea that you are doing with analyzing each rapid game. Thanks