Should You Accept a Smaller Reward or Risk It All for the Big Prize?

Thinking, after two-and-a-half hours of grueling chess.

Hello, Good Movers! You’ll never believe this, but I got to play against an actual adult human last week, instead of one of those pesky, underrated, terrifying teens. So, how’d it go? Did I rise to the occasion, or did I demonstrate that it’s less about the age of the opponent than it is the degree to which I am washed? Let’s find out!

Also: if you’re enjoying this newsletter, share it with your friends, family, and neighbors! And keep writing me to tell me what you think! I’ve gotten some nice notes over the last few weeks, which means a lot.

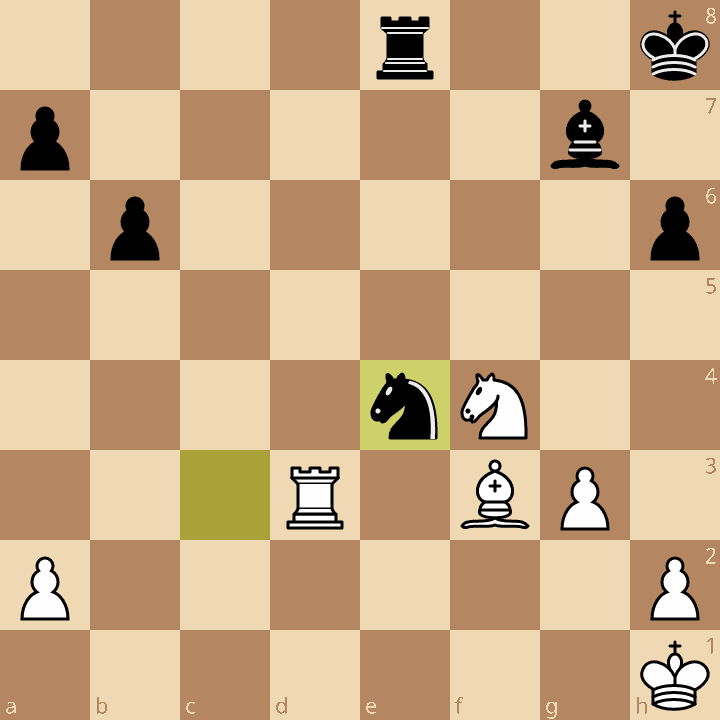

A Position.

Let me set the scene real quick. We’re in the San Marino Masonic Lodge, which is nearly empty. It’s about 9:30 pm, a good two and a half hours after our game began. Most of the players have long-since finished, packed up, and left.

My opponent — who, at 1745 USCF, out-rates me by 100 points — and I have been locked in a sharp and complicated battle. He had the edge out of a weird opening, and then I managed to develop some counterplay after he misplayed his queenside pawns, but he used a tactical trick to work his queen deep into my position. After a very uncertain series of moves, I succeeded in trading off a queen, rook, and knight, leaving us in a mostly equal endgame.

How am I feeling? I’m tired. I started with 90 minutes on my clock, and I have less than 15 left. I’m also relieved: for a while there, I thought I was in deep trouble, and I never felt great about my position during the game, which, for the second week in a row, took me out of my prep almost immediately.

So when my opponent took his knight, stuck it on e4, and offered me a draw, I found myself with an important decision to make.

I had a sense that the Ne4 move was a strange one, and that I might, all of a sudden, have some winning possibilities. But I also knew that I was fading mentally, and that I now had not just the chance, but the guarantee, of earning a draw against a higher-rated player.

This is, it turns out, a classic dilemma of psychology and behavioral economics. Do I accept the smaller but guaranteed reward? Or do I press on, confronting the risk of a heartbreaking loss in exchange for the chance of a greater victory?

In 1979, Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky developed the concept of prospect theory, which, drawing on evidence from controlled studies, concluded that most people suffer far more from a loss than they benefit from an equivalent gain: “For example, for some individuals, the pain from losing $1,000 could only be compensated by the pleasure of earning $2,000.” Kahneman further built out this idea in his extremely popular and influential book Thinking, Fast and Slow, applying it to wide swaths of everyday life, and he won the Nobel Prize in Economics in part because of it.

The real innovation here is the idea that we are not rational actors, and we do not behave according to, for example, the expected utility hypothesis of John von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern: we all have a unique “reference point” for assessing value in the choices we make, a reference point that does not reflect objective reality.

On top of this, the “certainty effect,” another understanding of Kahneman and Tversky’s that arose out of prospect theory, further demonstrates that we prefer a known outcome to an unknown one even if the unknown outcome would present us with better chances at gains.

So it isn’t hard at all to see how my situation maps onto this framework: I’m facing a certain outcome, an offered draw, or an uncertain outcome, playing for the win. Even though the win would offer a greater reward, it comes with far greater risk.

But this isn’t a decision happening in a vacuum: after two and a half hours of intense play, I’m almost certainly dealing with some level of decision fatigue, which I was well aware of as I sat there. Even if I was winning, which I didn’t know for sure, I didn’t trust myself to play optimally. Of course, my opponent probably wouldn’t either, and he had hinted at that by offering the draw; but while I knew that I was tired, I had no insight into how he felt.

After thinking for a minute or two, I took the draw. I behaved as Kahneman predicted I might: I accepted the guaranteed reward and chose not to gamble on the larger victory. When I got up from the board, I felt pretty good about this decision, even though there was a nagging thought in my mind that I might’ve had a generous chance of winning the game outright had I played on.

When I review my games, I usually go through without the engine first and make my analysis before I look at it with the computer’s help. But I’m only human: this time, I got into my car, recreated the position from memory and my score sheet, and plugged it into the chess.com analysis board on my phone.

Turns out I had a 1.25-1.5 edge, depending on the depth and strength of the Stockfish evaluation. There were definite, clear paths toward a victory. Seeing this, I could feel the familiar sense of regret creeping in, that ever-familiar post-chess phantom.

Here, of course, is the question, the rub, if you will: the friction that might bear the pearl. Knowing what Stockfish revealed, was I wrong to take the draw? Does this show that I’m some sort of mindless sap, a classic member of the sheeple marching along to the beat of Daniel Kahneman’s drum? Just another statistic in the annals of behavioral science? Do I need to start eating organ meats and taking ayahuasca so that I can ascend to a higher level of functioning and have the courage and fortitude and perseverance to grind it out to the very end if I ever want to live my best life?

Does this mean that, one day, I will die?

Now, let’s not go crazy here: obviously, I will never die, and neither will you. But it’s an interesting dilemma for a variety of reasons. The next time I find myself in a tightly contested endgame with the perception of an edge, should I go against my instinct to settle for the draw, knowing that it stems from some degree of risk aversion? Or is that an overreaction to a more complicated scenario — one that isn’t necessarily as cut-and-dry as “when you’ve got an edge, play for the win?”

I don’t even just mean in terms of my likelihood to convert the win or not, though that is a worthwhile question as well — after all, Stockfish is rated in the 3000s. Just because it sees something doesn’t necessarily mean it has any relevance to me.

Out of curiosity, I asked ChatGPT o1, “How often would you expect a chess player rated 1631 USCF to win an endgame in which he had a 1.25 evaluation advantage according to Stockfish?” It replied:

“It’s hard to pin down an exact number for how often a 1631-rated USCF player would convert a ‘+1.25’ Stockfish evaluation into a win, because real-world outcomes depend on many factors:

Type of endgame (e.g., a simplified Rook endgame vs. a tricky Bishop + Knight scenario)

Practical complications (passers, mating nets, time pressure, fatigue)

Player skill in endgames (some 1600s study endgames more than others!)

Tournament situation (time controls, psychological pressure, etc.)

[Editor’s note: all true!]

That said, if we look at broad statistical trends:

Top-level data (e.g., masters) suggest that a +1 to +1.25 advantage in an endgame is converted a majority of the time—often anywhere from 60% to 75%.

Club-level data (where 1600-ish players reside) show a more modest conversion rate, because mistakes happen more frequently.

A rough ballpark for a 1600–1650 player converting a +1.25 endgame advantage might be somewhere around 40–50% on average. Some players might do better if the endgame suits their strengths or if they have more time on the clock; others might convert much less often if they’re weaker in technique or severely fatigued.”

When I specified in this case that my opponent was 1745, it elaborated: “Against a 1745-rated opponent: the likelihood might drop somewhat—perhaps 30–40% or 35–45%, depending on the exact nature of the position.”

I asked it to cite the data for both the masters and club-level, and it admitted that both were “informed approximations,” so I think it’s worth acknowledging that these estimates could be off. But I’m inclined to think, for a variety of reasons, that they probably reflect at least something interesting re: the consensus online among chess writers and analysts, and what it reveals is that there is a significant — even likely — chance that I wouldn’t have converted the position. I would’ve expected these numbers to be more like 80-90 percent for masters and 60-75 percent for club-level players.1

What does this reveal? It reveals, first off, that chess, and by extension most endeavors, are far more difficult to do than they are to reflect on — that the mere act of seeing a scenario concretized or defined makes us almost incapable of placing ourselves back in the headspace of ignorance. This applies just as much to the making of art or the cleaning-out of a particularly disgusting garage as it does to playing chess: it is easy to forget, having completed the job, just how impossible it appeared as you stood on the precipice of beginning.

But it also points to one of the more interesting critiques of prospect theory that I’ve seen, which comes from David Kőszegi and Matthew Rabin. You might have noticed that terms like “suffering,” “benefit,” “gain,” and “loss” are all rather variable. Sure, if we’re talking about a situation involving money, then gain and loss can be objectified a little more solidly, but even then, $1,000 means a lot more to a struggling family of five than it does to Bill Gates.

This is, in a way, baked into Kahneman and Tversky’s theory, which accounts for the different reference points that any given person will bring into a situation. But Kőszegi and Rabin point out that the reference point isn’t merely different based on circumstances — it’s subjective, a product of expectations. If I expect to win a chess game, and I lose, I will be more disappointed than I would be if I anticipated the opposite result.

While this might seem obvious, it makes a major difference. Kahneman and Tversky demonstrate in prospect theory that people are not rational actors. True enough. But it goes further than that — not only are we irrational, but we live in worlds largely (entirely?) of our own devising.2 We need to interact with our expectations as much as we do our environment.

This is why self-honesty — being able to properly interrogate your own motivations and assumptions — is so important, and is a theme I keep coming back to in this newsletter. As far as “performance” and “satisfaction” and “not being miserable” go, it’s important to find success, but it’s also important to be setting proper expectations according to which you might succeed. If I expect to be a GM one day, then every step of my chess journey will be a disappointment. If I expect to improve, then that still might end in frustration. If I expect to learn from my games, though? That is within my own control.

Back to my game. Could I have won? Yes. Is “playing on” the decision that the ultimate chess-player version of myself would have made? Yes. Is that the proper way to maximize my potential gains and challenge myself the most fully? Yes.

But I had played that whole game expecting to lose. When I reached that point, I was presented with the guarantee of a draw. I had already won, relative to my subjective reference-point. On top of that, I was tired; I lacked confidence. To play on would have been to ignore the reality of my experience.

And going back to my larger expectations: I don’t expect to be a GM. I don’t need to maximize every opportunity to boost my rating. It was good enough that I had played an interesting and hard-fought game and avoided the loss. In the future, in similar circumstances, with this experience under my belt, I might be emboldened to fight for the win. But in this case, I’m pleased that I took the draw.

All of this made me think of the proverb, “A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush,” which seems, on its surface, to be a perfect reflection of prospect theory: you’d rather have the certainty of one bird than the uncertainty of two. But it turns out that, if you dig a little deeper into the proverb’s origins, you find that it might actually refer to falconry: the bird in the hand is, in fact, the falcon, which is an extracting-birds-from-bushes machine.

It isn’t just preferring one certain widget versus two uncertain ones; it’s about having a reliable method for producing widgets, rather than getting hold of two and not knowing where the rest might come from. In that sense, the phrase is actually more reflective of another one: “give a man a fish and you feed him for a day; teach a man to fish and you feed him for life.”

I appreciated that discovery, because it reinforces the project of this newsletter, which is to take my chess games and try to generate insights from them. Because it’s always nice to have the win — but it’s even better to have the wisdom.

Or maybe I’m just not that good at chess.

For what it’s worth, I asked Claude the same question, and its estimates were significantly higher: “Against a similarly rated opponent (~1600-1650), they would win approximately 65-75% of the time with a +1.25 advantage in an endgame; against a significantly stronger opponent (1900+), their win percentage would drop to around 40-50%; against a significantly weaker opponent (1400-), their win percentage might increase to 80-85%.” This is according to o1, the paid version of ChatGPT, and Claude 3.7 Sonnet.

For the drama, I then asked o1 what it thought of Claude’s response, and it said that it “struck me as optimistic.” (Italics the AI’s. I acknowledge that we’re getting a little off track here, but I find this fascinating and pretty hilarious.) o1 continued: “Ultimately, I stand by a more conservative figure (~40–50% or maybe 50–60% if you’re well-practiced), whereas Claude’s estimates describe a best-case scenario for a well-prepared 1600.”

So there you have it, folks: o1 stands by its assessment, other AIs be damned. If you’re allergic to AIs in general, then feel free to disregard this, but considering that chess is one of the areas of human endeavor in which we’ve been seriously using powerful AIs the longest, I’m inclined to be curious about their opinions more broadly.

This itself is a thread that can be teased out to quite great lengths: you can stop at, “Our thoughts play a role in impacting our health and happiness,” which science universally agrees on, or you can go as far as saying, “Our thoughts are the only things that are real,” which describes the philosophy of idealism as advocated by thinkers like Bernardo Kastrup. Either way, you’re forced to accept that the way you think about a situation is at least as important as what the situation actually is.

Next question, was getting you to think about evaluations and emotions instead of calculating why your opponent offered the draw?

Hey Kevin, I really enjoyed this post and its always WAY harder at the board, but the one thing missing is some analysis of variations. I haven't plugged this into an engine, but if you take on e4 and play Rook e8 check then re7 arent you just winning a pawn due to Nh5 or Ne6 threats? (Hence the +1.5 evaluation?) If thats correct you've got to play for the win, and shouldn't fear losing too much. (Again, easier said than done!) Keep up the great work.