Regular readers of this newsletter might have noticed something: I rarely win.

Over the course of Good Moves’ existence — 26 issues, shockingly! — I have only written about a game I won once. (And it was last year.)

Now, I haven’t only won once: my record through 29 OTB games before this week was 7-7-15. Still: that’s seven wins out of 29, or slightly less than one in four.

Now, there are good reasons for this, other than me being an irredeemable patzer (though that is certainly a factor). My club tends to divide tournaments into an over 1600 section and an under 1600 section, and with my rating consistently in the bottom half of the 1600s, I’m pretty much always one of the lower-rated players in my section — meaning that, most weeks, I play higher-rated opponents. And not just higher, but at least 100 points higher. (Interestingly enough, the likelihood of one player beating another who’s rated 100 points higher is… about one in four.)

Regardless, I’ve managed to scrape enough draws off of these better players that I’ve kept my rating in the upper section. On top of that, I’ve only lost to a lower-rated player once, and I’ve only drawn a lower-rated player once; my record against players rated lower than me is a respectable 5-1-1.

For the most part, I like it this way. I like playing higher-rated players, since it gives me the opportunity to test my skills and improve, and it minimizes the anxiety of getting upset by some underrated kid. (Much better to get embarrassed by some properly rated kid who’s just way better than me.) But, at the same time, I do sometimes get a little discouraged over how rarely I win. I’ve written in the past about how believing I can win games has been a major weakness for me, leading me to accept draws in positions where I have the upper hand. After all, drawing higher-rated players has gotten me this far, so I tend to default to it.

And yet: I’m not playing to draw. I’m playing to win. Fighting for wins has been a major focus for me lately. I’ve changed my openings and altered my study habits with this goal in mind.

Last week, that finally paid off — I earned a clean win against a player rated 1733, one of the better victories of my career. (I have two others against players in the 1700s.) But I’m not going to lie: rather than joy or excitement or pride, the main feeling I had afterward was relief. Finally: I won a game! I am capable! I can beat people in the section I’m playing in! It isn’t all pointless!

Being the neurotic writer I am, I noticed this reaction. And noticing it, I started to wonder: is there something less than ideal about my diet of higher-rated players? Is it possible that winning only eight games out of 30 could be holding me back from getting better?

In short: do I need to see the ball go through the hoop?

So what happened in the game?

First off, a little about the game. It was against a teenager who I’ve played three times before. We drew the first time, then he gained 200 rating points, and ever since he’d beaten me twice.1 Both of our last two games ended up turning into pretty closed, strategic struggles. But I had winning chances all three times, particularly in the first and most recent, so I went in to this latest matchup thinking I could win, and I tried to play with that attitude in mind.

Early returns were positive. I was better out of the opening, and then I focused on pins, which was the tactical motif I’d spent the week studying. Eventually, I had him in a tactical bind that was clearly winning for me. Unfortunately, I didn’t manage to find the move that would’ve given me a nice, flashy victory, but my positional superiority proved too much to overcome even as I finished out the game in a more conservative manner.

On top of that: I was out of book after move three — give me a break, I’m learning some new openings! — so the game backed up the conclusions in my most recent piece. Rather than struggling to remember a line and substituting something incorrect in its place, I just tried to read the board. I didn’t play the opening perfectly, but I played it better than my opponent, and that’s all that matters.

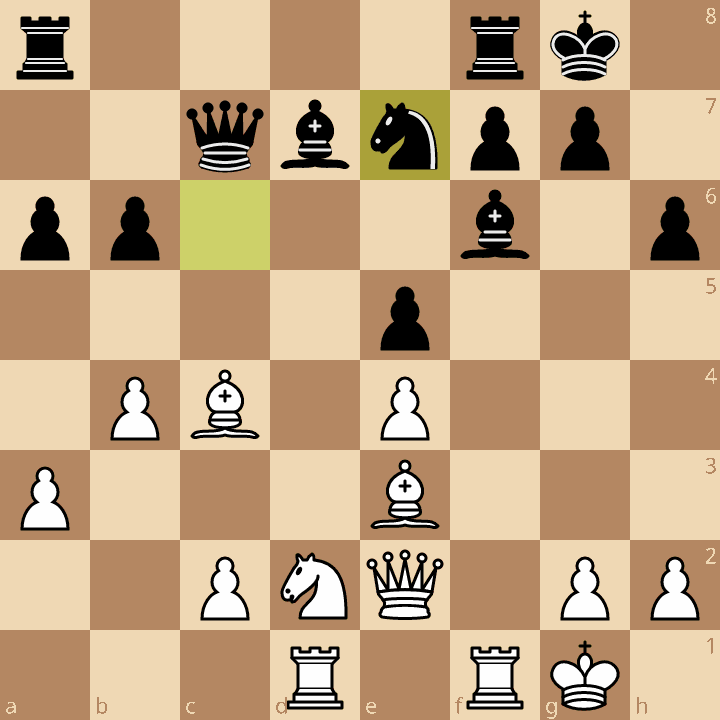

It’s interesting: part of the reason why I write so rarely about wins is the fact that I win so rarely. But another part is that it’s harder to write about wins than it is losses. The lessons are murkier. For example, if I had lost this game, I would’ve been able to tie it directly to missing that tactical blow that I highlighted above. But I missed the tactical blow and… I still won. My opponent wasn’t able to generate any counterplay, and then I found another tactic later on:

Even then, the move I played in this position — Bxh6 — isn’t the best one. Rxf6 is even better, because if Black takes back, their position is irretrievably busted: they’ve basically built a pawn wall between all of their pieces and the open king.

If you were trying to draw a lesson from this, you might say, “Hey, sometimes, you miss the best move, but you can still win!” But the problem with that is it isn’t really true. I’ve had far more games where I missed the best move and then I… lost. Sure, you should keep fighting, but that’s not really the point. Other days, I might’ve missed out on the full point.

But I didn’t. I won. And that’s the important thing, in and of itself.

On self-efficacy

In 1977, the psychologist Albert Bandura introduced the concept of “self-efficacy.”

Self-Efficacy is a person’s particular set of beliefs that determine how well one can execute a plan of action in prospective situations. To put it in more simple terms, self-efficacy is a person’s belief in their ability to succeed in a particular situation.

If you have low self-efficacy, then you’re going to assume that you’ll lose or fail at whatever you’re doing irrespective of the objective situation. If you have high self-efficacy, then you’re going to assume that you’ll win or succeed above and beyond the conditions on the ground. And most importantly, these beliefs have a direct influence on your performance: high self-efficacy makes you perform better, and low self-efficacy makes you perform worse. As Simply Psychology puts it:

People with strong self-efficacy tend to:

Embrace difficult tasks as opportunities to learn.

Recover quickly from setbacks.

Attribute failure to insufficient effort or poor strategy (things they can change).

Have lower stress and are less likely to develop depression.

People with low self-efficacy tend to:

Avoid challenging tasks or give up easily.

Focus on weaknesses and negative outcomes.

Believe failures are due to lack of ability (a fixed trait).

Experience higher stress and are more vulnerable to depression.

This might sound like self-esteem or self-confidence, but there’s a major difference: self-efficacy applies to a specific task. So I can have high self-esteem or self-confidence — I can even have high self-esteem or self-confidence when it comes to my chess abilities. But I might have low self-efficacy when it comes to over-the-board chess. This is an important distinction.

So what creates self-efficacy? Gulp: “Successful mastery of tasks is the most powerful source of self-efficacy information. Experiencing success strengthens beliefs in one’s capabilities, while repeated failures tend to undermine them.”

Now, this isn’t the only factor: seeing others successfully perform tasks, being told that you’re capable of being successful, and other physiological factors, i.e. anxiety or general confidence, can also have an impact. But… to believe that you can put the ball through the hoop, you have to see the ball go through the hoop.

You have to see the ball go through the hoop

When a basketball player is struggling, there’s often an easy cure: they have to see the ball go through the hoop. The idea is that, as soon as you remember that you can score, you’ll start scoring again. It breaks the curse. I have no idea when or where I first heard this, but it’s always stuck with me as a remarkably apt and direct way of describing confidence and performance.

It also perfectly reflects the concept of self-efficacy. To be effective, you have to believe, feel it in your bones, that you can be effective. And the best way to feel that is to have prior experience of it.

If I’m being honest with myself, I have to admit that all of the losses have started to take a toll. I don’t necessarily show up every week believing I can win. I do believe I can get a draw, but as soon as I see that higher rating, my assumption is that I’m going to lose or eke out the half-point. I tend to tell myself that that’s okay — that winning isn’t the most important thing. And there’s some truth to that: after all, I keep showing up even though my results are what they are.

But the problem isn’t that it affects my results: the problem is that it affects my performance, which is what I really care about. I play worse when I don’t think I can win. I’m more cautious, more conservative, and I give up on ambitious moves because I don’t think I can pull them off. If you scroll through the history of this newsletter, you’ll see piece after piece exhorting myself to take more risks, to be more confident.

The problem? I haven’t been seeing the ball go in the hoop. I haven’t had proof, over the board, that I could make it happen: that I could pull off the clever tactic or get the impressive win. I’ve tried my best to generate substitutes through online play, but it just isn’t the same. Instead, I keep urging myself to behave differently without necessarily believing deep-down that it’ll lead to better results.

Now, is there something I could’ve changed? I don’t know. I certainly wasn’t going to go down a section. In an ideal world, I would’ve found some other tournaments or situations where I could play a wider variety of ratings, but I barely have enough time to make this weekly game. Possibly, the answer was just to keep soldiering on until I got the result I was looking for. That might be different for you. Maybe there are ways for you to get some easy or more reliable wins at whatever your chosen focus is. If so, take advantage of it. Don’t just assume that grinding it out and taking your lumps is always the best answer.

Fortunately, this game provided me what I’d been missing, or at least a dose of it. The lesson isn’t that I can miss tactics and still win, or that I can improvise openings and still win, or that I can establish a superior position and win: the lesson is that I can win. I can hang with the folks I’m playing. I belong.

All I can do now is try to absorb that and carry it forward with me. Let’s see how I play when I think my moves might actually be good!

One of the funniest things about the club-chess dynamic is how you end up playing the same people over and over. This is the fourth time I’ve written about games I played against this kid!

Well it's gotta be 1. Bxf7+, right? Then 1...Kxf7 2. Qc4+ and if 2...Be6 3. Ng5+, if 2...Kf8 3. Ng5, and if 2...Kg6 3. Nh4+ probably leads to mate. 2. Ng5+ Kg6 seemed less clear to me, though probably also still good for White.

I'm glad to see such a positive outlook! Good luck on winning and growing your confidence in the future. I'd recommend trying to play more tournaments (just club ones if possible), just trying to get more varied opponents and rating levels (one of the problems with just playing a few people over and over is that you start to lose confidence when playing new people!). Also, check out this article: https://open.substack.com/pub/ambush/p/becoming-a-merciless-rakshasa?r=28ewo2&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false - seems a little weird at first, but just building up a confidence in yourself through a kind of persona has helped me a lot.